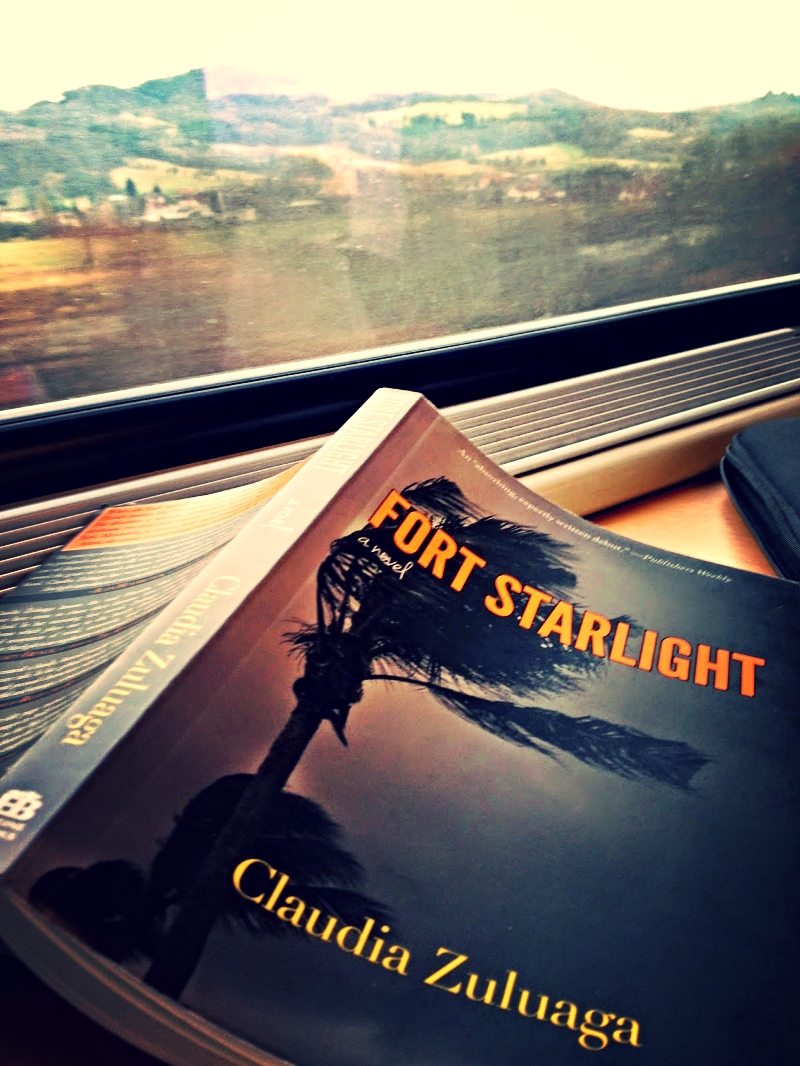

reading Fort Starlight en route to Prague

When traveling by train from Berlin to Prague, I began reading Claudia Zuluaga’s debut novel, Fort Starlight. Immediately caught up in the Florida tale of lost souls, swampland, and strangely discovered dreams, I was startled every now and then at the sight of cliffs and castles outside the train windows. Perhaps I was missing the sights of central Europe, but this is typical of me—I head off on adventures and find myself longing for home, which means “the South,” specifically the age-old stomping grounds of Florida. And so, Claudia Zuluaga’s words gave me permission to do just that, with a story that calls up uniquely believable characters, a vibrant and true sense of place, and just the right sway of narrative voice to carry the piece from start to finish. Engine Books’ editors, Victoria Barrett and Andrew Scott, have their sights set on fine writing, and Fort Starlight is among their many well-received titles. Curious about the author’s inspiration, the novel’s themes, and the astounding writing that adds Fort Starlight—by The New York Times Book Review’s standards—to the latest shelf of “Southern Literature,” I asked Claudia if she’d consider an interview, and I’m thrilled that she said, Yes!

Port St. Lucie, Florida

“past the beach houses built on stilts”

“Past the Beach houses built on stilts, past the ocean highway that runs along Erne City, past an inlet that is a shade lighter than the ocean, past more houses, past small streets, past the Florida turnpike, past dark clusters of trees, two North American blackbirds, male and female, fly west over the southeastern shore of the Florida peninsula.”-Claudia Zuluaga

The prelude to Fort Starlight—a novel about leaving the familiar and discovering the unfamiliar, about isolation and longing, about desperation and dreams—is one of place, and our first view, reminiscent of Eudora Welty’s opening passages in “A Curtain of Green,” is from above, an aerial shot of that place in Starlight County where the story will unfold.

The wetlands and heat and flat brilliance of Florida’s east coast are familiar to you, Claudia. Could you tell us a little about your background, how you, too, once found yourself in Florida, and why this setting is integral to your main character Ida’s story?

I’m the sixth of seven children. I was born in White Plains, NY. My parents, who had never owned a house, had bought a parcel of land in Florida around the time that I was born. I don’t think it was ever worth much, but the summer before I turned sixteen, when all of my older siblings were living on their own, they traded that plot of land toward the purchase of a villa in Port St. Lucie. At that time, Port St. Lucie wasn’t fully developed, and there was nothing but wilderness to the west of our planned community. Only maybe half of the villas were occupied, and for a teenager, pulled away from her friends and her pedestrian life, it was profoundly disorienting. And the heat. The whole thing felt like a dream. I would try to go for a walk, but five minutes in any direction was just swamp, tall grass, or asphalt, rippling in the heat. I spent most of that summer, after I gave up on the walking, inside the villa, in the air conditioning.

I was only fifteen, and my parents had put everything they had into starting a life there, but all I could think about was that everything I had known, all the people I had known, were gone, and I had to find a way to make something for myself, because I couldn’t imagine anything coming next. It seemed, at that point, impossible. And then, like Ida, I realized it was something I’d just have to survive, and that maybe I’d never know what it meant. But I did find things to hold onto. I made friends. I made it work as well as I was able. It didn’t take away my urge to escape, to undo what I felt had been done to me, but I found beauty there. It is beautiful.

North American Blackbirds

The blackbirds, first introduced in novel’s beginning pages, appear throughout, at first to show us the way and then, more than literary device, more than motif, they reveal their own story. Like the characters of Fort Starlight, they, too, are trying their best to survive the harsh and beautiful wetlands, “a place where anything dripping and new could step up out of the muck and begin its existence.” And inside the act of survival we witness the imperfections and vulnerabilities of the creatures and characters.

Would you expand on the importance of the world here, “the seven square miles of muddy rivers, scrubby trees, swamp, the forest hammock,” in relation to your characters and the intertwining stories?

The world of south Florida, of this wild part of south Florida that doesn’t touch the Atlantic, is something you can’t deny, can’t get away from. There is no ocean breeze to cool you off, no reassuring smell of salt in the air. It’s something that makes you think, “People probably aren’t supposed to be living here.”

But they are. And they are in Fort Starlight. Nature has pushed (almost) everybody inside to shelter, and inside is where they have to deal with their weaknesses, their problems, their pain. The place makes me think of a sweat lodge, somewhere you go to sit and sweat and suffer, all for the purposes of purifying, of moving forward.

A friend of mine says, “You can’t get away from your shit. It’ll track you down and eventually make you deal with it.” Everybody in Fort Starlight is at that place in their lives. They can’t run any longer. This is what unites all of the characters. This is the basis of their community, whether they know it or not.

“An alligator could snap you up in two seconds”

“the body of… a twelve-year-old boy is guarded by a thirteen-foot alligator”

As I read Fort Starlight, I noticed the idea of imperfection casting itself into the storylines, and in each successive chapter, with subtlety and great care, the perfection of imperfection beginning to fold itself into scenes in which characters interact with each other and with nature. Careful narrative threads, crosscutting, and lyricism work together and create a landscape in which the perfection of imperfection is revealed. Pairings appear: Ida and her long-lost brother, Peter and the memory of his wealthy father, the at-odds gay couple Ryan and Lloyd, the neglected and wandering boys Donnie and Carter, Nancy and her terminally ill great-niece, even the body of twelve-year-old Mitchell Healy and a four-hundred-pound alligator, and yes, the blackbirds.

What might you tell us of the meaningful isolation and imperfection of your characters and of the physical, emotional places in which they find themselves?

I wanted to make Ida stuck, with no easy way out. The only way she is going to grow, meaningfully, is by being stuck with herself. It is so tempting to think that everything will change, if only you pack up and move away from the familiar, if only the background and the noise and the weather are different. Of course, it’s not that easy. The only things that change are the background, noise, weather. As soon as the disorientation has dissipated, you are back where you started.

Despite the difficulties that Ryan and Lloyd are having, that Nancy and her great niece are having, that even the boys are having, they all have each other for support in their journey. Ida has only the imaginary companionship of her brother. Peter has only the memory his father and the illusion of his superior intellect. These two are the most in need of figuring out who they are and how their lives are going to be, and both are brave about it, if a bit misguided. They have to be alone, until they don’t anymore. And I see their relationship—one of parallel growth rather than intimacy—continuing beyond that last moment at the beach.

Florida tree house

Tidal pool, tree house, or a beachside table spread with a sunset supper of cold white wine and deep-fried gator?

I’m torn between the tidal pool and the tree house. When I was in high school, we would go to a beach called Bathtub, and when the tidal pools were full and warm, at night, we’d bring goggles. You could swim in some of these pools in darkness, without having to worry about riptides or sharks. There were these phosphorescent organisms, and if you moved your hands underwater, watching with the goggles, it was like you were parting the stars. Amazing.

One of my brothers moved to Florida for a few years, around the time I moved out of my family’s home, and he and his wife did live in a tree house for a time. It was tiny, dark wood, with bunks instead of beds, no real furniture. Something from a fantasy movie, like The Dark Crystal or Labyrinth. It wasn’t open to the elements, but it was up in a tree, up over swamp water, cozy. He moved there with his wife, just after they were married.

Florida map

Claudia, you’ve lived in the South, and your writing, so far, concerns the South, a place that for many, including myself, has a mystical, powerful, sinkhole kind of attraction. There are the harsh realities of hurricanes, overzealous religions, and unsettling heat, and then there are the gentler ones of salty ocean breezes, herons in flight, the taste of grilled pompano.

Do you find that you are drawn still to writing mostly about Florida? What is it about this particular setting that inspired you to write the Pushcart-nominated story, “Okeechobee,” and then the much-praised novel, Fort Starlight?

There is something in the very shape of Florida that makes it feel cut off from the rest of the country, the rest of the world. Once I moved there, I never once drove up and out of the state. It just seemed so far. We’d go south, west, east. Never north.

I moved to an efficiency near the beach just before I turned nineteen, and then to Orlando for a few years, where I worked as a waitress. As a matter of fact, I didn’t leave Florida until I was twenty-one and flying out on my very first airplane ride. I’ve never been back to my home town. Not even once. Miami, the Keys a few times, but no more Treasure Coast. This wasn’t on purpose. I didn’t really feel I had roots there, and even my parents gave up and moved back north, because none of their children lived down there.

That isn’t to say that Florida doesn’t have culture or joy or possibility, because of course it does. I think my feelings about that particular part of Florida were really colored by the fact that, when I did live there as a teenager, I was under the thumbs of my strict parents, and I had no car or freedom. I was away from everything I’d ever known and believed the rest of the world was gone; there was no evidence of it anymore. I couldn’t even go for a walk, because there was nothing to walk to. I couldn’t get my bearings, really. All of this combined made me really disoriented and unsure about how to figure out who I was. I fled, thinking I needed the distraction of other people to be able to figure it out. Maybe I did.

Now, I’m a grownup, I can drive, and there’s the magic of the internet, connecting everybody. The place I lived, as I knew it then, doesn’t exist anymore. I wouldn’t experience it the same way.

I didn’t realize I had to get it out of my system, work through what it all meant, until I was in the noise and chaos of New York City. People have described my writing as atmospheric, very setting-oriented. I’m not sure if that is the case in anything I write that isn’t based in Florida. I think I may be done with Florida, but who knows! I have other Florida stories, one called Be Your Animal, published in the now defunct Lost Magazine.

Okeechobee

Trailers & Palm Trees

At David Abrams’ literary blog, The Quivering Pen, you wrote of earning your first paycheck for a story accepted by Narrative Magazine. I love the humor and honesty of this account, and even more, I love the story itself. “Okeechobee” is a sweet, sad short-short about how childhood and family are rough and rare.

Would you tell us something about the narrator, a young girl who notices the world around her—her own version of Florida—in terms of the tension between her parents, the hot afternoon of canned colas and closed trailer doors, curses and class differences and broken-down cars?

Kids take in what they are ready to take in. There is an age when children start noticing the things that are not right about their lives, not right about their families. They start to imagine what their own life will be like someday, and this causes them to notice and judge and long for what they don’t have. My narrator has just begun to have this awareness. She sees the tension between her parents, the lack of joy, affection, spontaneity, and starts to put the pieces together, trying to figure out where it all came from, trying to figure out what it means for her.

My second summer in Florida, I had a boyfriend who seemed to be, at the time, the only thing I had going for me. Naturally, he dumped me. I was despondent, because I had thought I’d found some direction, something to hold onto that made me who I was. If I mattered to someone, then I was connected to the world. The dumping happened around the time my mother wanted to visit her friend in Okeechobee, and though I was a mess, she made me come. Maybe she thought it would cheer me up, or maybe she just was wary of leaving me home alone. We got in the car and drove, meeting her friends at a rodeo (where they did, I think, have warm cans of cola). It was so hot. I thought it was supremely ugly. I sat with my shoulders hunched, too numb to cry.

A bull collapsed. People rushed over, then just stood over it, watching while the beast’s heart gave out. It seemed that there could be no more miserable place on earth at that moment. Hot and dusty, warm soda, a heartbroken girl, a dying bull, all of this happening even closer to the center of the state, where there seemed to be no escape. Why had my mother made me come? Did she not understand my despair? There was definitely something about the disconnect that inspired the story of Okeechobee.

“Small fishes, sand, bits of seaweed, scallop shells, whole and cracked”

And finally, I want to acknowledge the ending of Fort Starlight without giving it away. There are moments of resolution I feared might become too carefully tied, and so I was relieved that the characters and their story lines remain a bit smudged, as well as lovely and imperfect. Ida’s character expands exponentially once she finds the Atlantic, and as in the beginning, she experiences a new place with “tide pools on both sides… the water… so clear… [she] can see the bottom… Small fishes, sand, bits of seaweed, scallop shells, whole and cracked… a stingray in the last… just before the sand bars end and the open ocean begins.” Here, there is a widening, the possibility of moving forward, the moment Ida and all Fort Starlight’s characters have longed for. Is this perhaps where you as a writer also found a place from which to move forward? And from this easterly view, where are you headed next?

Yes!! I am working on a novel right now that goes to an even more challenging place for me, emotionally and psychologically. Before Fort Starlight, I wouldn’t have had the courage to jump into the strange, unknowable thing I’m jumping into now. Now I trust the process of writing a novel and know that it will work itself out, as long as I keep at it. Fort Starlight was a mess for years. I had all of these pieces and had no idea how they connected. For the longest time, I couldn’t figure out who Ida was. I would see her doing things and I didn’t know why. All I had was atmosphere, and it took so long for the people to emerge from this atmosphere, and this is echoed in the prologue with the bit you excerpted: “a place where anything dripping and new could step up out of the muck and begin its existence.”

So I’m looking east, yes. At the deepest, darkest, most unknowable trenches of the ocean. With my fingers crossed.

CLAUDIA ZULUAGA

Photo Credit: Christian Uhl

Claudia Zuluaga is an English Lecturer at John Jay College (CUNY) in New York City. She received her MFA in Creative Writing from Sarah Lawrence College. Her short stories, which have been nominated for Pushcart and Best American Short Stories, have been published in Narrative Magazine, JMWW, Lost Magazine, and Linnaean Street.

*

The Poppy: An Interview Series

Four to six questions begin as pods, then burst open with answers, bright lapis,

black-stamened, conspicuous—ornament, remembrance, opiate.

*

First posted at Hothouse Magazine.