“While he lamented the shipwreck that was his marriage, he mourned the equally disastrous changes in his old route. It was no longer the road of his blissfully rudderless youth, when this stretch was a wild and untamed curve of the bay, dotted with signs of warning—“Swim at your own risk” and “Caution, strong tides”—which had only encouraged recklessness. This area had once been so sparsely settled that, at low tide, he and his older brother, Nod, could walk the few rocky miles from their house to their dad’s office without ever touching the civilization of the sidewalk. They loved the damp band of earth that was neither wholly sea nor entirely land, a constantly changing landscape that offered their prepubescent souls new, exciting dangers to overcome. Duncan and Nod had felt themselves gifted at avoiding the perils of the seaweed slicks. They had leaped across the cracks and crevices with ease, even grace, and had waded unafraid through tide pools full of barnacles and crabs. They had scratched their bare legs on wire lobster traps and tripped on minefields of trash, surviving to tell the tale. As boys, they were masters of their world, demi-gods of the water’s edge. Now their infinite kingdom was gone.”–JoeAnn Hart

JoeAnn Hart writes about environmental concerns that affect coastal regions, where sea and land meet, and where ecosystems are made even more fragile by man’s irresponsible pursuits. Her characters are observant and engaging, her prose layered with metaphor, her setting lush with realism, and her themes linked to the beauty and tragedy of the natural world. In this interview she speaks of her novel, Float, and the environment, as well as community and collaboration.

JoeAnn, tell us about your background. Has Gloucester always been your home? And how has that coastal landscape influenced your writing?

I grew up in the Bronx, then Westchester, before escaping to the Rocky Mountains, which is where young people went in the 70’s. Most of New York was cavorting about in Boulder, including the man who would be my husband. He was from Manhattan, but had just inherited a creaky house in Gloucester, and so I was dragged, somewhat kicking and screaming, from the sunny mountains to the icy sea. It was January, 1979. The sky was gray, the snow was gray, and the harbor was frozen over for the first time in decades. It was no Coastal Living magazine spread. I was only 22, and I wasn’t sure I had the fortitude for maritime life, but love being what it is, I stayed, and Gloucester became a part of me, and me of it. I didn’t start writing until much later, when the working waterfront had already begun its decline. The fisheries were decimated by the industrial fleet with their bottom-scraping trawls, and plastic debris was becoming the main harvest in the nets. In Float, I’ve tried to come to grips with the crippling of the local fishing fleet, and the ecological devastation of the seas. Most writers attack these problems through journalism and other non-fiction formats, but I am comfortable writing about these issues in fiction. I believe that environmentally conscious fiction can forge a strong connection between the brain and the heart, and become a catalyst for social change.

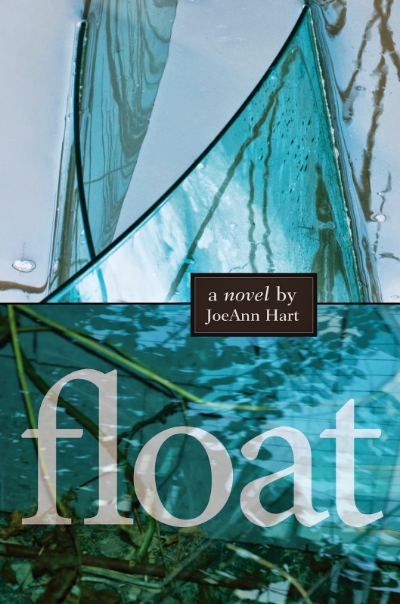

JoeAnn Hart’s novel, FLOAT – Art by Karen Ristuben / Design by John Yunker

“A wry tale of financial desperation, conceptual art, insanity, infertility, seagulls, marital crisis, jellyfish, organized crime, and the plight of a plastic-filled ocean, JoeAnn Hart’s novel takes a smart, satirical look at family, the environment, and life in a hardscrabble seaside town in Maine.”

I love this description of Float. Would you tell us the details of what inspired you to write this novel? And how you decided on the title and on Duncan Leland, the man whose “infinite kingdom” is facing rising tides, as the character through which the story is revealed?

As with my first novel, Addled, I started out with the title, Float, then dove in to play with all the many different meanings and images. The concept of Float began when I heard a friend tell me what her therapist told her, that she had to learn to float over her stress, that she couldn’t struggle against every crisis or else she would get pulled under and drown. So she learned to just say the word float whenever she was stressed and it helped get her through. I thought that was brilliant, and started building on it. I developed a main character, Duncan Leland, who had both his personal and business life in jeopardy, then I gave him a crazy mother to boot. Through the course of the book, he must learn to float, or sink. I used ‘float’ not just in this psychological sense but also in its financial meaning, as in, to float a loan. Then there are the things that float in the ocean, such as plastic, or dead humans. A float is also a wooden platform connected to a dock by a ramp, and it moves up and down with the tides. Not to mention, floating on air.

Tidal pools, salt marshes, or white-capped seas?

Since I am a total wimp, no white-capped seas for me. I enjoy watching them from a distance, inside. Near a fireplace. And when I think salt marsh, I think greenhead flies, who will rip the flesh off your bones during breeding season. There are a few toe-biting crabs scuttling along the bottom, but you won’t ever find a shark in a tide pool.

JoeAnn Hart with Daisy – Photo credit: Morgan Baird

What has been the most memorable harbor sighting from your dory? And does Daisy, your rescue pup, share these fair-weather outings?

The most wonderful part of rowing around the harbor in a silent vessel like a dory is the seals. They are as curious about us as we are about them, so we – me and my rowing partner, Sarah – always have an eye out for a mammalian head peeking out of the water. It is amazing to think of these large animals, these air-breathing animals like us, living under the ocean’s surface. It is not just a parallel universe to ours, but a completely foreign landscape, and here is an ambassador from that country – a seal – saying hello. To them, we are a dark lozenge shape moving slowly over their heads. They see the tips of our oars enter the water, then disappear. What are we doing, they wonder. What are they doing, we wonder. Daisy doesn’t come on the dory with us – she much prefers luxury motor yachts with staff – but when I walk her on Brace Cove and it is low tide and the seals are sunning themselves on the rocks, they seem to know one another. The seals arch up, as she goes by, and stare. Perhaps they feel their vestigial leg bones twitch, just a little, as they watch her jump from rock to rock.

You are active in the Gloucester writing community—including the Gloucester Writers Center and the Rocky Neck Art Colony—as well as environmental alliances and animal rescues—NAMA: Northwest Atlantic Marine Alliance, Save Your Ass Long Ear Rescue, and more. It seems you’ve found a way to traverse the worlds of art and environment. Collaboration is also evident in your choice of artist Karen Ristuben’s cover image for Float, and your partnered gallery reading/artist discussion this September. With your past, present, and future endeavors in mind, is the environmental path of your writing career ever overwhelming? Or does the support of community and collaboration keep you energized and inspired?

In almost all cases, I get back more from an organization than I give. Usually, that pay-back is in the form of satisfaction of having at least tried to make a difference in the world, especially when it comes to the environment. There is also the payback of connection. I’ve met wonderful people working with groups. I’ve also met a few clunkers, but it’s all grist for the mill. Humans just crack me up. We say one thing, and do another, and we almost always work against our own best interests, especially when it has to do with the environment. Here we are, a species destroying our own habitat, and we just continue on our way as if it’s not happening. So I have nothing but admiration for organizations that keep fighting the good fight even as we’re sinking. Especially the arts and humanities, which are too often viewed as if they were an accessory to our culture, and not the defining aspect of our species. Science can make us think, but the arts make us feel, and in order to make the right decisions for the future of the world, we need to use the whole brain, not just half of it. We should all try to approach the world with the wonder of an artist and the curiosity of the scientist. Gloucester artist, Karen Ristuben, who did the cover art for Float, has this sensibility, so I was thrilled when Ashland Creek, who specializes in environmental literature, chose her photographs for Float. We were on a panel together this summer with other environmental artists and writers – Kyle Brown and David Abrams – to talk about how the arts can be used to enhance environmental action. It was the hottest night of the year in an un-air-conditioned space, and we had a packed house, which demonstrates a great deal of interest in the collaboration between the arts and the environmental sciences.

NAMA is important because they promote local fishing in the same way that the plight of the family farm was brought to our attention. We can fish and save the fish at the same time if we have the right international policies, and if people understand where their fish comes from and how it is caught. And of course, Save Your Ass is close to my heart because we got Abe and Zach from them. We love our donkeys, and we like to think they love us too.

JoeAnn Hart – Photo credit: Brendan Pike

JoeAnn Hart is the award-winning author of the novels, Addled, (Little, Brown) and Float, (Ashland Creek Press), a finalist for the Dana Award in the Novel, and an excerpt of which won the Doug Fir Fiction Award. Her work explores the relationship between humans and their environment, natural or otherwise. Recent stories, essays and articles have appeared in The Sonora Review, Newfound Journal, and The Boston Globe Magazine.

Photos by JoeAnn Hart, Morgan Baird, and Brendan Pike.

*

The Poppy: An Interview Series

Four to six questions begin as pods, then burst open with answers, bright lapis,

black-stamened, conspicuous—ornament, remembrance, opiate.

*

This interview first posted at Hothouse Magazine.