Road trip to New Orleans by way of Clarksville, Tennessee, Oxford, Mississippi, and Jackson, Mississippi. Was it a literary pilgrimage? It didn't start out that way.

The first day posed rain, then promised downpours. Cincinnati and Louisville with their impossible strands of traffic provided the worst weather. I simply slowed down, easing through the gray walls of water, and let the truckers and impatient SUV drivers pass.

I had decided to stay with a friend in Clarksville. Little did I know I was headed into the Tennessee River Valley where flash floods were in progress. I exited the big, wide highway - the safe highway - for the little, winding country roads of Kentucky, heading straight west into more rain and a few quick stops to gas up and gawk at the straight edges of simple poverty. Traveling alone, these sorts of things pluck at my anxiety. Western Kentucky made me uncomfortable, made me feel stupid and unknowing and resistant. I was happy to fly over the border into Tennessee, into the roads swollen with muddy pond water, the rivers rising all around. Really, until I pulled onto the road where signs read, Birthplace of Robert Penn Warren, I had no idea of the flooding. My friend's apartment was just off that road, and closer to high water. She was on the second floor, and our cars were parked beyond on even higher ground.

That night I asked her about her writing and the conversation came back to famous writers, like Robert Penn Warren. Warren was born in Guthrie, Kentucky, schooled eight miles over the border in Clarksville, Tennessee, and later attended Vanderbilt. I thought about his Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, All the King's Men, and remembered where I was heading: Louisiana, my home, with its diminished delta, its shores moving inward, oil refineries and fisheries fast neighbors, its statesmen still questionable, though Bobby Jindal would never have anything over Huey P. Long.

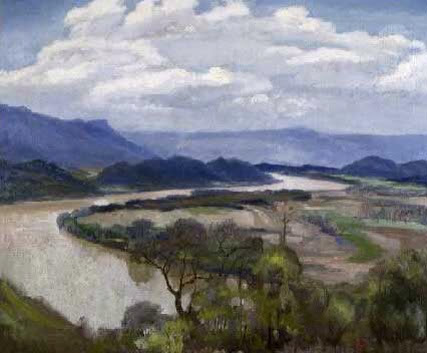

The next day I drove more little roads, alongside, but always higher than the rising, rushing waters of streams and rivers. I came to a place where the signs weren't clear and pulled into the parking area of a small bank. I realized for the first time how the land was so brilliant and green. Purposeful flooding back in the thirties - the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) - displaced more than 15,000 families, in order that the dams could harness hydroelectric power. Nearly seventy-five years later, the valley ribboned out in lush, verdant lines. I drove on, amazed.

Farther along, I saw an egret alone in a flooded field, a lilac balloon tied to a fencepost, an abandoned barbeque stand, a single yellow butterfly, and the velvet swathes of green, green fields against the hot blue sky. Things became apparent. Jackson, TN meant Jesus. Bolivar, TN meant pretty and poor. From Hickory Valley to Grand Junction, Tennessee's Hwy 18 proclaimed itself "National Bird Dog Highway." Near the border of Mississippi, a hillside of worn-down cows, horses and their babies, and sorry-looking donkeys all grazed together.

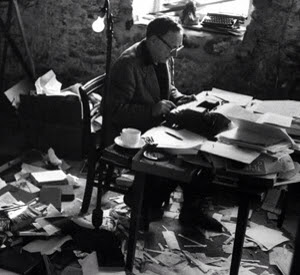

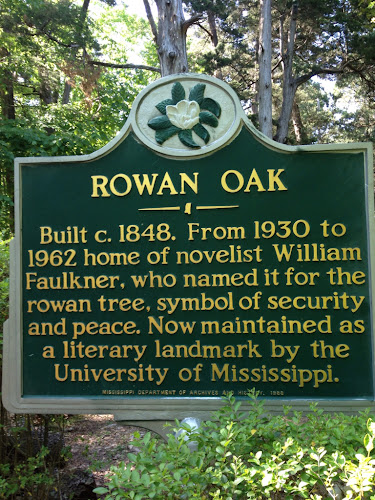

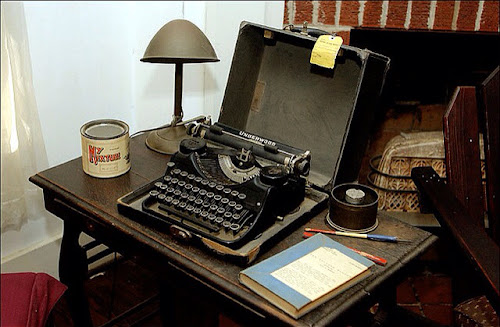

Crossing over into Mississippi, the fields quickly became cypress swamps and the roadside became frighteningly barren with blight and rusted trailers and permanently parked trucks. Signs read: kudzu-control. All I could think was, "Get me outta here." And once Hwy 18 became Hwy 7, the blight gave way to bright red clover, waving welcome all the way to Rowan Oak and Mr. William Faulkner's front porch, the Ajax Diner and a bottle of Lazy Magnolia Southern Pecan Ale, a shaded bench just outside the Oxford courthouse, and Square Books where I picked up a copy of Suzanne Marrs' What There Is to Say We Have Said: The Correspondence of Eudora Welty and William Maxwell.

That evening I sat outside on a rocker on the long, luxurious porch of The 5 Twelve, the bed and breakfast on Van Buren, only blocks from Oxford Square, thinking about the lost art of letter-writing, and a line of lanterns floated past over the treetops, amber and aglow in the darkening sky.

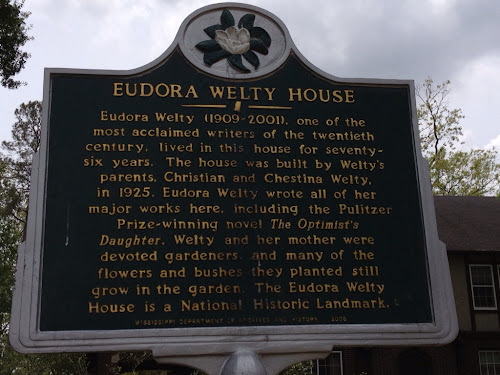

The next morning, south of Oxford, MS, I passed graveyards, green corridors of pine and oak, the road growing poorer as I headed south. Just before Jackson, my air conditioner went out on me, but I was pulling off the road anyway, to visit Eudora Welty's home and to walk through her mother Chestina Welty's garden. The only one on the tour, I heard stories and stories from the young guide, an English Lit major just about to graduate from Belhaven, the college directly across from the Welty house. I'd once been an English Lit major with no idea of the future. And so, I was in good company.

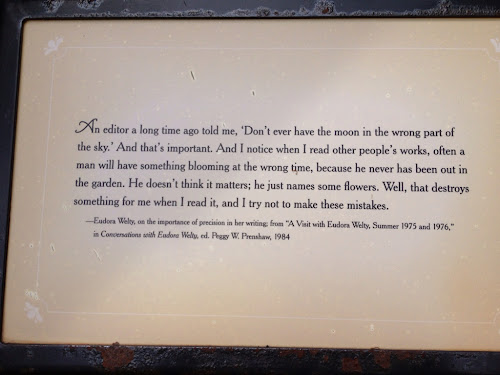

The house was solid, with large rooms, bookshelves everywhere. Even so, Eudora placed many of her books in stacks, little stacks of five or six, and I wondered if there was rhyme or reason to the arrangements. One included Virginia Woolf and Dante and V.S. Pritchett, along with a few unreadable spines. The books lined couches, the dining room table, side tables, and in some rooms, the floors.

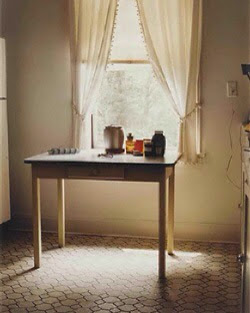

In the kitchen I stood, astounded, remembering the William Eggleston photograph I'd seen in the Gund Gallery at Kenyon College in Gambier, Ohio the previous summer. There I was, standing smack in the middle of the photograph. Nothing had changed. We stayed in the simple, bright room a while, my guide telling me things. The most memorable about a story Eudora rewrote from memory. After The Southern Review editor, Robert Penn Warren, rejected the story, Eudora threw it straight into the kitchen's wood stove. Yes, it burned right up. Her only copy. And you'll have to go on the tour to find out which one.

I hated to get back into the hot car, but there were miles and miles to go. The pouring rain in McComb, MS cooled the air by twenty degrees. No AC? No problem. Now I had only to worry about tornadoes and rain whipping my windshield. Eventually, the Mississippi pines gave way to Louisiana cypress swamps, and I bucked along the raised sections of I-55, fishermen's shacks and shrimping boats to one side, cattle egrets flying overhead. And finally, finally, I found the flooded streets of New Orleans. Writers and roads had guided me all the way. I was home.