THE FROM-AWAYS - A Novel of Maine

An Interview with CJ Hauser

“THE FROM-AWAYS,” CJ Hauser’s extraordinary first novel, encompasses the relationships of old-timers and newcomers in a small coastal town in Maine. Here, subjects as diverse as historical preservation and economic progress, along with ideas of love and trust, loss and belonging, shift and fit together. From the first scene of setting lobsters free to the final moments of bell buoys and safe return, the novel reveals itself as “a novel of Maine.” Leah and Quinn, two twenty-four-year-old women who write copy and drink whiskey, are “the from-aways”—outsiders, newcomers—to the town of Menamon, looking for their place in the world, and over the course of a year, they learn how much they belong.

CJ Hauser is very aware of PLACE in her writing, as revealed in many of her stories, from “ABANDONED CARS,” the winner of the THIRD COAST’s 2012 Jaimy Gordon Prize in Fiction, “THE SHAPESHIFTER PRINCIPLE” in TIN HOUSE, and “A BAD YEAR FOR APPLES” in TRIQUARTERLY. Place can be as noisy and hot as summer in Flatbush, as undone as the scorched interior of a car, or as in “THE FROM-AWAYS,” it can be as inviting as a Christmas tree lot complete with hot cocoa in hand, as a quilt-lined dinghy rocked by gentle waves. “THE FROM-AWAYS” invites us to know hardship as well us comfort, and does so with enormous expressiveness via the viewpoints of Quinn and Leah.

Lobstah

“I have two lobsters in my bathtub and I’m not sure I can kill them.”

— Opening line of “THE FROM-AWAYS” by CJ Hauser

CJ, I love the first line of “THE FROM-AWAYS.” Immediately, we know where we are—Maine!—and a New York City girl with a large heart is about to set her supper free. It’s like a different version of the scene in “ANNIE HALL.” No chasing lobsters around the kitchen; instead, Leah’s having a beer with a pair in the bathroom. There’s humor and a beautiful introduction of Leah’s relationship with her new husband, Menamon native, Henry Lynch. How did you decide on the opening scene? Were there influences from your own life that inspired you here?

I love that you bring up “ANNIE HALL,” because that scene is so wonderful, and of course was an inspiration to me. But I think that opening truly grew out of one summer when I was a nanny on Rhode Island. I was supposed to cook the kids lobster while their parents were out to dinner…but I’d never actually cooked a lobster before—my father had always done the cooking—and so I had these lobsters out on the counter and the kids were yelling from the other room and I found myself about to cry because I had no idea what I was going to do. Then, this friend of the kids’ parents, a trouble-making, blustery older guy from Mississippi who insisted I call him “Uncle Richard,” came waltzing into the kitchen and said, You’re doing it wrong! And I said, I haven’t even done anything yet! and he said, That’s your problem, not doing anything.

He showed me how to cook them, a method that involved pots of sea water from the bay, and beer, and lobster-belly tickling, and both of us drinking chardonnay.

The lobsters came out perfectly—but the kids wouldn’t eat them. They took one bite and said lobster was gross and so I made them butter noodles instead and Richard and I ate the lobsters and everyone was happy. Why aren’t you at dinner with the grown-ups? I asked Richard. He said, I’ve never much cared for grown-ups.

“THE FROM-AWAYS” – by CJ Hauser

The structure of “THE FROM-AWAYS” relates to the seasons—the book moving from “Summer” to “Summer, Again”—and relationships—as revealed by Leah and Quinn’s alternating chapters. Leah and Quinn each have their reasons for moving to Menamon—Leah, to become part of Henry’s life, and Quinn, to rediscover the father she’d lost in childhood. What were the reasons for choosing seasonal markers and characters new to the town to tell this story?

Maybe I’m just homesick because I live in Florida now, but up north the seasons feel so important to how we live in the world. Every winter, sometime around March or April I’d start to give up all hope for life and feel like tossing myself from a window. And then every June I’d think everything is so wonderful I might explode and I couldn’t even remember what winter was like. I think New England summer might have the same effect on the brain that the chemical cocktail new mothers get hit with does… You know, where they feel so full of love and happiness that their memories of the pain of childbirth are dulled and fuzzled so they’ll forget the bad parts and remember the good and be more likely to do it all again?

This may sound extreme, but so is a New England winter.

It felt impossible to tell a Maine story without seasons. It was also important to me to show that this takes place over the course of a year because Leah and Quinn both want to make changes in their life so quickly. Leah wants to be a local in Menamon and comfortable in her marriage, and Quinn wants to be grieving her mother less keenly and to form a relationship with her father… But these things can’t happen quickly. There’s a German word I learned by way of Emerson: naturlangsamkeit. It means the slowness of nature. Both women in the book have to learn to let things grow and die at their own natural pace.

Backshore Afternoon – by Joshua Adam

“Because you cannot always know with love.

If we knew how things would turn out for certain,

knew a person completely, that would be far too easy.”

— Leah – “The From-Aways” by CJ Hauser

Relationships, especially occurring in pairs, are central to the novel: Quinn and Leah, Leah and Henry, Quinn and Carter, Leah and Charley, Quinn and Rosie, and so on. Ideas of trust and love, honesty and lying, forgiving and growing up arise within the various formulations of these pairings. Leah and Henry begin and end the book, and it’s lovely how their relationship develops, particularly in that we learn this through Leah’s perspective. How did you discover her sensibility—from her humor and her anger to her eventual understanding of her marriage and her place in Menamon?

Honestly, I think that in the first draft of this novel Leah was a lot more competent and kind and that just wasn’t very interesting at all and I knew something had to give…

I once had a relationship where I just felt like I was failing all the time. Everything I did was wrong. And I learned a lot of things from that. I learned to sometimes stand up and yell I AM NOT WRONG THIS TIME! MOST OF THE TIME BUT NOT THIS TIME! But I also learned that there were a lot of things about being in a relationship I didn’t know how to manage, and that there was a lot of sacrifice and synchronicity required to pull one off.

In the following drafts of the book I gave this experience to Leah in an amplified way and suddenly she was no longer nice or competent. She repeats throughout the book that she is “good at many things,” until it becomes a kind of protest-too-much refrain and we realize that she knows she’s trying but failing to be good, most of the time. As we all are.

Including all of Leah’s mistakes and selfishness made writing her more difficult… but I hope it makes her character more honest too. She is not necessarily a blanket-likeable woman, but I hope that a lot of readers will see the truth in her and respond well to that.

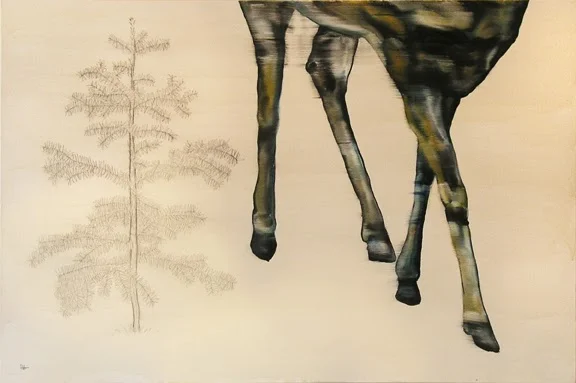

“Totem, Houligan’s Gulch” – by Joshua Adam

The novel’s complications push past individual concerns to larger ones, each piece fitting into the story and then moving it forward. Quinn will eventually meet her father, the famous musician Carter Marks, and discover her own talent for music; Leah will decide where she stands, even if in disagreement with Henry; and the town will gather in the local bar and on the town green to work against the forces that threaten a longtime way a life. When juggling all of the parts that create a whole—in light of character arcs and plot lines, pivotal moments and scenes—how do you keep track?

I cannot tell you how much I wish I were the sort of writer who had a master plan for plots and characters—but I’m not. Honestly? I invented the place and the people and the relationships… seeded some conflicts… and then I figured out how they all worked together from there. Which is to say, it’s like I bought a bunch of ingredients and decided what meal I could cook with them, instead of having headed to the store with a recipe in hand.

I don’t recommend this. I’m trying to be more intentional and scheming with my next project…. but maybe some of our brains just don’t work that way. I’ll let you know how it goes…

“I watch this solar system of tiny revolving bodies orbiting Rosie’s head.”

— Quinn - "THE FROM-AWAYS” by CJ Hauser

Imagery plays a role in terms of the characters. Quinn describes Rosie in a halo of light with moths circling and landing in her hair. Quinn says: “All I want to do is stare and stare at this girl’s face, and yes, I really am in trouble now. Bad trouble, I think as I watch this solar system of tiny revolving bodies orbiting Rosie’s head.” Leah speaks of Henry in similar ways: “the moon” like a marker, “the deep orange color of wild honey,” illuminating their marriage, its brightness “too bright,” fooling them with its reflection. Tell us how you come upon imagery as it relates to your characters.

There are lots of reasons to write, but for me, most things begin with an image. Blood-brown lobsters in an old bathtub. A moon hanging low so it looks like its sitting on a hill. A swarm of moths around a head. Someone fingering a glass taxidermy eye their pocket. These are things I see in my head and I want to make them so that other people can see them too. I used to draw and paint a lot because of this same urge, but GOOD GOD was I a terrible painter. I don’t code images as symbols, and I seldom enjoy work where writers work with images as symbols first and as visceral things second. It’s a gut thing. And if you get it right, the meaning will follow.

“I’m not really a New Yorker in a dinghy anymore.”

— Leah – “THE FROM-AWAYS” by CJ Hauser

Belief in belonging is something Leah and Quinn share as “the from-aways,” while trying to find their way in Menamon. Quinn understands this as framed within the family picture, a family perfect in its imperfections. And Leah finds she’s “not really a new Yorker in a dinghy anymore,” how she “may have gotten a late start but it is not too late… to belong to this place.” Is the idea of belonging one you visit now and again in your writing, or is it a newer concern? What are other ideas that call to you and inspire your fiction?

I worry a lot about geography. I grew up in a little New England town to which I very much belonged. I felt at home there and had family ties there back some years. But, as I’ve gotten older, I’ve realized I’ll likely never live there again, and while it’s exciting to think I could live anywhere, I wonder what I’ll lose by not staying at home. Sometimes I think this means I’ll never get to feel like belong to a place again. When I say belong, I mean you can describe who lives in every house and what the snow there tastes like and you know what day in May the dragonflies will emerge for their yearly insect orgy and that every godforsaken thing in the place you see kaleidoscopically, like it’s shattered into all the different times you’ve seen it over the years and you can see all those times at once. A depth of experience, I guess, is what I’m talking about. But maybe there’s something to leaving all that behind. To starting fresh. It sounds very liberating, actually. And I like to imagine that if I do someday live in a new place, I’ll have to learn all that stuff from scratch. Probably from the people who are from there. I will probably have to learn it through stories those people will tell me. And that, actually, sounds pretty wonderful.

Recently, I’ve been thinking a lot about the way certain stories resonate through time while others get lost. I’ve been thinking about how stories work with time and what stories might look like in the future. And all this is part of the jumble that I’m working on for my next book, which is going to be an adaptation of one of Shakespeare’s comedies.

Eagle Island Bell – by Joshua Adam

Bell buoys, lobster pots, or coastal carousels?

Bell buoys, forever and always.

Thank you, CJ, for this wonderful conversation! And for all of the readers here, spread the word! “THE FROM-AWAYS” is a beautiful debut novel and even includes Maine recipes, a familiar jukebox playlist, and the more in its final pages.

CJ Hauser

CJ HAUSER is from the small but lovely town of Redding, Connecticut. Her fiction has appeared in TIN HOUSE, THE KENYON REVIEW, TRIQUARTERLY, AND ESQUIRE, among other places. She is the 2010 recipient of McSWEENEY’s Amanda Davis Highwire Fiction Award and the winner of THIRD COAST’s 2012 Jaimy Gordon Prize in Fiction. A graduate of Georgetown University and Brooklyn College, she is not in hot pursuit of her PhD at the Florida State University. Though ever and always a New Englander in her heart, CJ currently lives in a small white house under a very mossy oak in Tallahassee, Florida.

Images and author photograph with permission of CJ Hauser.

Images of Joshua Adam’s oil paintings, including the feature photo, “Boathouse at the Point,” with permission of artist.

Visit The Adam Gallery in Castine, Maine.

*

The Poppy: An Interview Series

Questions begin as pods, then burst open with answers, bright lapis,

black-stamened, conspicuous—ornament, remembrance, opiate.

*

First posted in the Arts section of Hothouse Magazine.