SYBELIA DRIVE ARCs have arrived, pre-order links are up, & only two months to go until the novel’s release date of October 6th! Artist & true friend, Annie Russell, created the most beautiful cover I could ever imagine, & the Braddock Avenue Books creative team coordinated design, edits, & all the rest. When I started writing this novel, I wrote on a dare, I wrote to answer questions I’d had for decades. LuLu showed up, then Rainey, & of course, Saul. I wandered after them into the citrus groves of childhood, trying to know the bitter scents of fallen fruit, of fathers & sons sent away to war, of mothers trying to make ends meet. I’d love to share their story, so here is the PRE-ORDER LINK. Braddock Avenue Books, the small press that gave this book a home, will benefit the most from pre-order purchases. From now until the beginning of October, they’ll earn 50% of the sales price, but once Amazon takes over, the press will earn a little less than a dollar. Pretty sobering. Is it a leap of faith to ignore discounts & convenience? I hope so. Braddock Avenue Books will thank you, and so will I! Plus you’ll get a memorable read, or the most gorgeous doorstop you’ve ever seen, and my ever-loving gratitude. 💕🌸

Points of Connection

A Conversation with Bich Minh Nguyen

“In August 1965 a woman named Rose walked into my grandfather’s café in Saigon.

That much is known. My grandfather would say that’s the beginning of this story.

My mother would say I should have left it at that.”

So begins Bich Minh Nguyen’s much-praised second novel, “Pioneer Girl.” As in her memoir, “Stealing Buddha’s Dinner,” and her first novel, “Short Girls,” thematic points of connection–places of origin, family relationships, and comforts of food–are laid out before us, each influencing the next, each as important as the others. These points are textured by differences between the first and second generations of immigrant families, the feelings of belonging and not belonging, and the weight of lives that lead from east to west, all the while anchored in both places.

These points of connection are exactly what I love about Nguyen’s books. There is the sense of geography, which spans from Vietnam to the Midwest to the West all the way to the Pacific, which leads back to Vietnam. There are the relationships, close and distant, caring and complicated, between sisters, grandmothers, fathers, uncles, grandfathers, mothers, brothers, and friends. And then there is the food: from all-you-can-eat childhood comforts to the more mature market-grazing of peaches and oysters, white wine and lemon-lavender cake, and throughout the years, the love of banh mi and cha gio and pho and, ultimately, the shared love of eating.

Nguyen approaches these elements with the consideration and concern of a scholar, yet invites her readers in with the ease of a storyteller, her intricate narratives threading through terrain that is as tough as it is touching, revealing characters we come to care about.

“Pioneer Girl” by Bich Minh Nguyen

Thank you, Bich, for agreeing to this interview. You’ve had an incredible year, what with the publication of “Pioneer Girl,” moving from your longtime home in the Midwest to the Pacific Coast, and joining the MFA in Writing Program faculty at the University of San Francisco. Do you see a parallel between your own move to the West Coast and the travels of the narrator, Lee Lien, in “Pioneer Girl,” as well as those of Rose Wilder Lane, the mysterious subject of concern in the novel?

Thanks for inviting me to do this interview!

I wanted to write a book that brought together some of my enduring obsessions: the immigrant experience in the United States; the “Little House on the Prairie” books; and bad food in small towns. In “Pioneer Girl” the city of San Francisco becomes hugely significant to more than one character; it was also the place where Rose Wilder Lane, Laura Ingalls Wilder’s daughter and editor/co-author, became a writer in the early 1900s. When I wrote “Pioneer Girl,” I’d been living in the Midwest for years. I also grew up in Michigan and have spent more time in the Midwest than anywhere else. I had no idea I would leave. But by the time the novel was finished and edited, I had accepted a job in San Francisco. I think what I share with Rose Wilder and Lee Lien is a sense of restlessness, or at least an understanding of that feeling. Neither Rose nor Lee wants to “bloom where they are planted”; they want to roam. They feel the tug of family obligation but also the longing for adventure. I felt many of these complications myself, growing up in a small city in Michigan in the 1980s.

The Midwest

For some, small-town America, as in Sherwood Anderson’s “Winesburg, Ohio,” generates a feeling of distress, of feeling trapped and wanting to escape. Your novel, “Pioneer Girl,” and your husband Porter Shreve’s novel, “The End of the Book,” in a way a sequel to Anderson’s book, approach this idea of entrapment with the sensibility and firsthand knowledge of town life in the Midwest.

Lee Lien, of “Pioneer Girl,” questions her family’s choice to remain in the Midwest, once they settle in the Chicago suburbs and open their own café, after years of moving from town to town through a series of Asian buffet jobs. In “Stealing Buddha’s Dinner” you wonder at your father’s strength in bringing your family to the Midwest after the Fall of Saigon and at his decision never to leave. Do you think the Midwest will always inform your writing?

It’s true—Porter and I both wrote novels that deal with real-life literary figures, family duty, and the Midwestern feeling of isolation. We didn’t read each other’s work until we had pretty solid drafts and even then, it took us a while to realize we were on similar thematic tracks. I think it must have been because we were both in the midst of questioning where we were, geographically. We had ended up in Indiana for academic jobs and we had two young kids. We’ve both moved quite a bit, but having kids made us more anxious about where we wanted to be. The back-of-the-mind questions became daily ones: Are we going to stay? Do we want to live somewhere else? Where? What are the risks, gains, and consequences of leaving and starting over? Inevitably, these questions also came out in our writing and in our characters.

I’m sure the Midwest will always inform my writing because I am essentially Midwestern; it’s where I grew up and it’s what I know. One of the aspects of geographical identity I wanted to explore in “Pioneer Girl” is how our childhoods are made by other people. As children, we have no control over where we live or where we grow up. But it informs so much and, as adults, we contend with it. Lee contends with it against her mother’s expectations. Rose Wilder hated growing up in Mansfield, Missouri and couldn’t wait to leave. My father gave me and my siblings the best childhood he knew how to give, and it started with his decision to leave his world behind and start over in the United States. No move I make could ever be so bold and brave. Now that I have kids, I am even more in awe of the burden and responsibility involved in his decision.

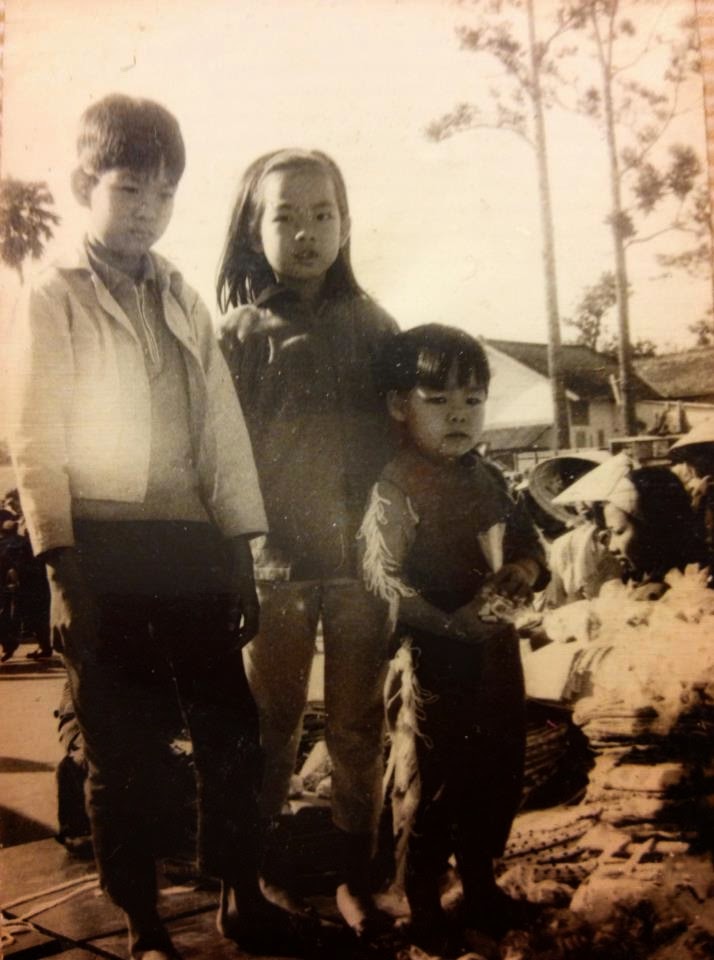

Bich, Anh, and their dad – Grand Rapids, Michigan – mid-1970s

In “Pioneer Girl” you have created remarkable moments between the first- and second-generation members of an immigrant family. You’ve shown the conflicting sense of guilt and sense of responsibility, as well as the loyalty and memories that bind one to family. The daughter Lee’s relationship with her mother is seemingly no-win, the mother always disapproving, criticizing. Yet Lee tries to imagine why her mother is this way, and generosity, understanding, and compassion rise above feelings of shame, anger, and guilt. The grandfather, Ong Hai, is nonjudgmental, always understanding and optimistic, always caring and loving without agenda. His is true unconditional love. And the brother, Sam– first-born, the son, “spoiled”–separates himself from family by disappearing.

Could you comment about these relationships, how you found a way to describe them so deftly, focusing on each character, keeping their wants and needs distinctive and yet tied together, so that family remains the true collective sum of its individual members?

I wanted to explore the way people take on certain roles in a family and how sometimes those roles are given. You know—that’s the artsy kid, that’s the athletic kid, that’s the good one, that’s the wild child. These identifiers can be only partly true because they’re too reductive. But once they get made they can be hard to shake; they can end up becoming self-fulfilling prophecies. Yet everyone has a secret self, a set of secret beliefs and feelings: this is who I really am, and no one else knows it. Lee feels this for herself, but it takes a while for her to realize that’s true of everyone else in her family too. She thinks she knows her mother so well, but there are, of course, hidden wells. The same goes for Sam and Ong Hai.

I also wanted to explore the way families make their own myths. Laura Ingalls Wilder and Rose Wilder did that through the “Little House” books—and they fought quite a bit while working on them. Most families have internal and often passive-aggressive struggles for power: who gets to control the narrative of the family story? In “Pioneer Girl” Lee’s mother seems to be in control, but Lee begins to question that. She does and does not want to be the good daughter. Obligation is inescapable in most families, I would guess, and not just Asian ones. And it’s a major factor in the conflict between the first and second generations in immigrant families. I wanted to find ways to show that conflict emerging, not just in big fights, but in everyday interactions.

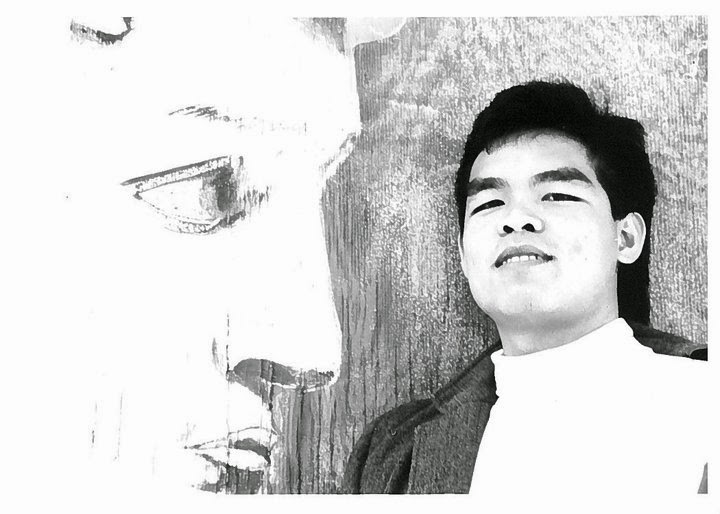

Bich and her sister, Anh

“Short Girls” by Bich Minh Nguyen

Early in your novel “Short Girls,” the chapters alternating between two sisters’ viewpoints, the character Linny has a moment of understanding and empathy for her older sister, Van. She “thought of her sister driving through her subdivision in Ann Arbor, decelerating, directing the car into the driveway. She pictured Van just sitting there, almost unwilling to move. How well Linny knew that feeling… a mixture of relief and dread. Now I have to get out of the car, she thought at those times. And she always did, even though she dreamed of driving on without a map… For the first time, it occurred to Linny that maybe her sister had fantasized that very same thing.”

Would you speak about your process of approaching the tougher, more emotional concerns of relationships, especially between siblings?

Fiction writing requires empathy and understanding. In many ways, that’s why we read and why writers are born out of reading: we want to understand the lives and experiences of other people. “Short Girls” was partly inspired by my own relationship with my two older sisters and partly by Jane Austen’s “Sense and Sensibility” (a book I’ve loved since high school). My sisters and I aren’t much like Marianne and Elinor, or like Linny and Van. But we had, as those characters do, our ups and downs, our arguments and resentments. I remembered always trying to figure out my sisters when we were growing up. Why won’t they play dolls with me anymore? Why are they listening to that same Led Zeppelin record over and over? How do they know how to behave as girls? Do they like me? Are we going to get along today? I wanted to apply these feelings toward Linny and Van. They have to figure out how to see each other not just as sisters, bound by the common, irrefutable bond of a shared childhood experiences, but as people who are in some way essentially unknowable. By the way, I should say that my sisters and I get along great; it’s just much more interesting to explore the conflicts!

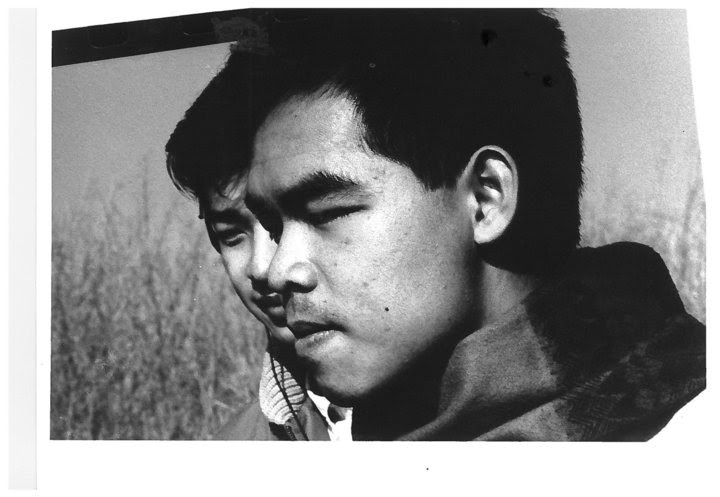

Noi and her sons

Bich, Anh, and their grandmother, Noi

Food, family bonds, and identity are recurring themes in your writing. One example of how these themes come together, and in which you pay beautiful tribute to you grandmother, Noi, is in the chapter “Cha Gio” of “Stealing Buddha’s Dinner.” When Noi prepares the ingredients of cha bio for Tet–the grated carrots, fish sauce, black pepper, mung bean noodles, the ground shrimp and pork–you recall the “forkful of filling on a triangle of banh trang spring roll wrapper,” Noi’s laughter and how later she would “pluck the cha gio from the frying pan,” and “the first anticipated bite, the sweet and peppery flavors of shrimp and pork and fish sauce weighted against the delicate crunch of the fried wrapper.” In Noi’s cooking there is love, as seen in the lines: “I ate slowly, trying to memorize the flavors, trying to know what my grandmother has always known: this amount of pepper, this amount of fish sauce. She had always been there to show me this world without measurements.”

Would you tell us more about how the world of tastes and meals, both Vietnamese and American, was influenced by family and friends, creating new ties and strengthening or complicating old ones, and how all this shaped your identity?

Food keeps appearing in my work because I think about it all the time! Don’t most of us? What should I have for breakfast, lunch, dinner? What’s in the refrigerator? Where should we eat? What should I make? I love thinking about food and reading about it; I love fulfilling a craving. I think I ended up writing “Stealing Buddha’s Dinner” because I realized that food was an expression of longing in my childhood, a marker for cultural and social contexts. At home, we ate Vietnamese food. Out in the world of small town Michigan in the 1980s, no one was eating that; they were eating peanut butter and jelly, Chef Boyardee, Hamburger Helper, and casseroles. So much of my experience growing up was about trying to figure out where I fit in as a child of immigrants. I felt totally American, yet could never “look” American enough; I was also Vietnamese, yet knew almost no Vietnamese at all. My relationship with identity became very complicated, but somehow my relationship with food did not. I loved Vietnamese food; I loved American food. No matter what else was happening around me, as long as I had the right food at the right time, then everything was going to be at least a little okay. I credit my grandmother Noi for instilling in me a great appreciation for good food. She truly enjoyed it—the process of cooking, the art of opening a pomegranate, the daily ritual of dinner—and so I did too.

“Stealing Buddha’s Dinner” by Bich Minh Nguyen

“Throughout my childhood I wondered, so often it became a buzzing dullness, why we had ended up here [in Grand Rapids, Mich.], and why we couldn’t leave. I would stare at a map of the United States and imagine us in New York or Boston or Los Angeles… I was convinced people were happier out on the coasts, living in a nexus between so much land and water.” – from “Stealing Buddha’s Dinner”

Bich, now that you’ve landed decades later with your immediate family in San Francisco, a city on the Pacific Coast, do you feel a sense of happiness and possibly a connection—geographical, spiritual, or otherwise—to the distant coast of Vietnam?

I probably felt that way, growing up, because when you live in the Midwest you’re always being told that you’re in the middle of nowhere. Flyover land. But the Midwest—Michigan, Indiana, Illinois—is where I’ve lived the most, and it wasn’t my life’s goal to move to New York or San Francisco. When the opportunity came up, my husband and I really debated it. It freaked me out, really, to imagine living on the west coast, in the Pacific time zone, far from everything I’ve known. Now we’re here in the East Bay and I’m still getting used to it in a sense—getting used to the fact that I chose to change my life. And that our kids are going to be Californian, which seems so strange. I wouldn’t say that living here gives me any particular connection to Vietnam or anything like that. But I do feel more comfortable, by which I mean normal.

Lemon-lavender cake, Twinkies, or a Top Pot hand-forged doughnut?

Lemon-lavender cake. I do love doughnuts though, and almost all kinds of homemade cakes. I love making old-fashioned bundt cakes and layer cakes.

And finally tell us something you’d like to be asked – from inspiration to breakfast to bliss!

Why the obsession with Laura Ingalls Wilder?

When I was a kid I read those “Little House” books until I practically memorized them. I loved the descriptions of food, the cozy evenings, the ongoing battle of farmer versus nature. When I reread the books as an adult, it occurred to me that maybe I loved them because the experiences of the Ingalls family—pioneers moving westward, homesteading, in the 1870s—was not unlike the experience of immigrants moving west to America. They’re parallel stories of heading out to unknown places and starting over. Though Laura and I had nothing in common on the surface, I felt a kinship with her. She knew what it was to be restless, to be shy and bookish, to want to stand out while also wanting to hide. She had longings for certain foods and material comforts. She had a great frenemy. She had secret rebellious thoughts. When I started researching the origin of the “Little House” books, I learned that her daughter Rose had heavily edited, perhaps even co-written, the books. Rose is an obscure figure now, but once upon a time she was more famous than her mother. And late in life she went to Vietnam, as a journalist, in 1965. When I learned about that literal connection between the “Little House” series and Vietnam—this was probably twenty years ago—I knew I would one day write something about it. I just didn’t know what it would be.

Bich Minh Nguyen

Bich Minh Nguyen’s most recent novel is “Pioneer Girl.” Her novel “Short Girls” was an American Book Award winner in fiction and a LIBRARY JOURNAL Best Book of the Year. Her memoir-in-essays, “Stealing Buddha’s Dinner” received the PEN/Jerard Award and was a CHICAGO TRIBUNE Best Book of the Year and a Kiriyama Prize Notable Book. Nguyen received an MFA in creative writing from the University of Michigan and has taught in the MFA Program at Purdue University and the MFA Program at the University of San Francisco. She has also coedited three anthologies of short stories and essays. She and her family recently moved to the Bay Area.

*

All photographs with permission of Bich Minh Nguyen.

*

The Poppy: An Interview Series

Four to six questions begin as pods, then burst open with answers, bright lapis,

black-stamened, conspicuous—ornament, remembrance, opiate.

*

First posted in the ARTS section of Hothouse Magazine.

Andrew Lam: A Voice from the Heart

This is the second part of an interview with Andrew Lam–journalist, essayist, short story writer. The first part precedes this one and is titled: “Andrew Lam: Language, Memory, Bliss.”

Is there a childhood memory that you return to again and again?

Let me tell you a story. In 2003 a PBS film crew followed me back to Vietnam, and in Dalat, a small city on a high plateau full of pine trees and waterfalls, they coaxed me into revisiting my childhood home. The quaint pinkish villa on top of a hill was now abandoned, its garden overrun with elephant grass and wildflowers.

We broke in through the kitchen and, once inside, I proceeded to explain my past to the camera. “Here’s the living room where I spent my childhood listening to my parents telling ghost stories, and there’s the dining room where my brother and I played ping-pong on the dining table. Beyond is the sunroom where my father spent his early evenings listening to the BBC while sipping his whiskey and soda.”

I went on like this for sometime, until we reached my bedroom upstairs. “Every morning I would wake up and open the windows’ shutters just like this, to let the light in.” When my palm touched the wooden shutter, however, I suddenly stopped talking. I was no longer an American adult narrating his past. The sensation of the wood’s rough, flaked-off paint against my skin felt exactly the same after three decades. Heavy and dampened by the weather, the shutter resisted my initial exertion, but as before, it gave easily if you knew where to push. And I did.

The shutter made a little creaking noise as it swung open to let in the morning air–and with it, a flood of unexpected memories.

I am a Vietnamese child again, preparing for school. I hear my mother’s lilting voice calling from downstairs to hurry up. And I smell again that particular smell of burnt pinewood from the kitchen wafting in the cool air. Outside in my mother’s garden, dawn lights up leaves and roses, and the world pulses with birdsongs. Above all, I feel again that sense of insularity and being sheltered and loved. It’s a sentiment, I am sad to report, that has eluded me since my family and I fled our homeland in haste for a challenging life in America at the end of the war.

Living in California, I had heard much about holistic healing and talk of long-forgotten emotions being stored in various parts of the body; but I had never truly believed this until that moment. Yet, it’s hard for me now to deny that there’s yet another set of memories hidden in the mind, and the way to it is not through language or even the act of imagination, but through the senses.

In America I used to speak of the house with its garden, and my childhood, as a kind of fairy tale, despite the war. Sometimes I would dream of going into the house and taking shelter in it once more; at other times I would dream that nothing had changed, that the life I had left continued on without me and was waiting impatiently for my return. In nightmares I saw it as it was–empty and gutted, and I was a child abandoned within its walls. I would wake up in tears. After so many years in America, I continued in my own way to mourn my loss.

Until, of course, I reentered the house again, and emerged with an unexpected gift–a fragment of my childhood left in an airy room upstairs. Now back in America I feel strangely blessed. I don’t dream of the house in Dalat any longer, or rather when I do, it has changed into another house.

Having touched the place where I used to live once more, I can finally say what I had wanted to say after so many years: Goodbye.

Andrew, your uncle, a singer, who remained in Vietnam after the war ended, talked to you of writing about those who left and those who stayed in Vietnam and of writing with a voice from the heart. Could you speak a little about writing with “a voice from the heart”?

My uncle was a propaganda songwriter for Ho Chi Minh’s army during the Vietnam war, so he belonged to the communist side, the winning side. Now he’s in his 80s, a dissident of sorts, writing about corruption and governmental failures. So he understands deeply about regrets and the need to write and create true art from the heart. He was deprived for years from publishing romantic ballads. His closet is full of songs that have never been sung.

So his advise was very much welcome. He said, “Writing is no joke. You must observe the world keenly and the things that affect you, move you, you must process with your eyes, your head. Then you must find a way to speak with your heart. Because only when you speak from the heart, can you move the hearts of others.”

I understood that long before his advice, but when I heard it, I felt validated. I renewed a deep connection with this estranged uncle–we, the entire clan, all fled to the West, and he was the only one left in Vietnam. I never write from the head–I write about things that move me and hurt me or make me sit up in wonder. My writing is best when they make me laugh or cry or shake my head in happiness with a certain tone, certain turn of phase, as if I am the reader myself. Use your head, your eyes, but yes, always speak from the heart.

All photographs: permission of Andrew Lam.

Andrew Lam is the author of Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora, which won the 2006 PEN Open Book Award, East Eats West: Writing in the Two Hemispheres, and most recently Birds of Paradise Lost, his first collection of short stories. Lam is editor and cofounder of New American Media, was a regular commentator on NPR’s All Things Considered for many years, and the subject of a 2004 PBS commentary called My Journey Home. His essays have appeared in many newspapers and magazines, from The New York Times to The Nation. He lives in San Francisco.

*

The Poppy: An Interview Series

Four to six questions begin as pods, then burst open with answers, bright lapis,

black-stamened, conspicuous—ornament, remembrance, opiate.

*

This interview first posted at Hothouse Magazine.

Andrew Lam: Language, Memory, Bliss

“When I was eleven years old I did an unforgivable thing: I set my family photos on fire. We were living in Saigon at the time, and as Viet Cong tanks rolled toward the edge of the city, my mother, half-crazed with fear, ordered me to get rid of everything incriminating… When I was done, the memories of three generations had turned into ashes. Only years later in America did I begin to regret the act.”

– from “Lost Photos” – October 1997 – Perfume Dreams - by Andrew Lam

Andrew Lam—journalist, essayist, short story writer—reflects on the world in the way only one who has lost his homeland can: with compassion, understanding, and a global stance. His essays, personal and poignant, examine the Vietnamese diaspora and the bridges and barriers between hemispheres, while his story collection defines the idea of exile in completely new ways. Here, in the first installment of this two-part interview, Lam responds with depth and detail.

Your first languages are Vietnamese and French, and you write in English. It’s not surprising that voice and language play an enormous part in your stories. Do you think your aptitude for these languages carries into your fiction?

Absolutely. I fell in love with the English language, learning it while going through puberty. I am told that children learn foreign languages in the same primal part of the brain as their native tongue, but by high school it becomes a challenge, as brain plasticity has been lost. But in learning a language, your voice breaks, when plasticity is still available and language is both primal and not. That’s how it felt for me. Learning English changed me inside out: I was growing, and my voice broke, and I spoke in a new voice, with a new timbre. It was a kind of enchantment and I never fell out of it.

It helped, of course, to speak Vietnamese and French first. I hear the music in each language, the varying cadences, and the intonations used in different parts of the throat, the mouth, and the nasal area. I can hear voices from many of my characters very clearly – which makes writing short stories like writing plays. And, as an essayist of twenty years, I can hear my own voice very clearly, which makes it less troublesome to write in the third person narrative, that is, when using my own voice for the omniscient viewpoint.

I think I know the answer to this trio of questions, given your travels as a journalist, but readers here might not. And so: Have you ever made a literary pilgrimage? What were your experiences? How did this journey influence your writing?

An interesting set of questions, and the answer to the first is both yes and no. I never intentionally go on literary pilgrimages but have been to places where literature plays a profound role in the experience. Hanoi’s Temple of Literature, for instance, is one of the most beautiful temples I’ve ever visited. Etched on fading tablets atop giant stone turtles are the names of the Mandarins, those of enormous talent and will, who passed the Imperial exams, written as poetry forms, over a thousand years ago. I felt a kinship with these names, for I know the effort to stay awake in late evenings or early morns to write the next sentence, to hear aloud the cadence of your own voice, to get one more line in before darkness takes over.

There are places that remind me of books I’ve read. The Notre Dame de Paris of my childhood brought the memory of reading Victor Hugo’s “The Hunchback of Notre-Dame.” A promenade on the Thames and a visit to Shakespeare’s theatre, The Globe, made me recall “Prospero” and “Romeo and Juliet,” and imagine myself in the audience when the plays were first staged.

At my literary agent’s home in Boston, I was shown some of his prize treasures: door knobs that once belonged to Somerset Maugham, and, of course, I had to touch them, and felt—at least in my own imagination—their razor’s edge.

In Belgium once, through a chance invitation to a castle, my hostess—a Vietnamese woman married to the baron—prepared pho soup and the aroma perfumed the ancient halls. She gave me Vietnamese books to read. It was strange feeling: to be both at home and in a completely strange setting.

But perhaps nowhere have I found the act of writing more powerful than in the Whitehead Detention center in Hong Kong, where I covered the stories Vietnamese refugees who, at the end of the cold war, were facing forced repatriation. The experience became part of my first book, Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora. But it was there, more than two decades ago, that I witnessed the act of writing as a desperate attempt toward freedom. People who were being sent back to communist Vietnam to an uncertain future wrote and wrote. As papers were hard to get, they told their life stories in tiny words so as to save space on a page. They wrote without having an audience. In the end, many gave me their diaries, their private letters, their testimonies and poetry to take out of the camp. These stories, told as a way to convince the UN of their political prosecution at home, could not be taken back to Vietnam, as they would ironically become evidence that they were “anti-revolutionary.” On the other hand, these writings were not admitted by the UN as evidence of those persecuted in Vietnam. I translated and published a few pieces, but the rest sat for years in my closet, a reminder that for some, refugees and persons who sit in a cell, writing is bleeding.

Who are your favorite writers?

I have been influenced by James Baldwin, Joan Didion, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Vladimir Nabokov, Kazuo Ishiguro, Richard Rodriguez, Maxine Hong Kingston, and so many more. I identify with books that I love, and I love these writers for particular books they’ve written.

What is your idea of absolute happiness?

No one asked me this question before, at least, in this particular phrasing. I am not preoccupied with happiness, absolute or partial. It seems to me that it is a conditional state, subject to its opposite, grief and sorrow. Of all these feelings, I’ve had my share. But I will say that for perhaps as long as I can remember, even as a child living in Dalat, Vietnam, my preoccupation is with freedom, in the Buddhist sense. In respect to literature and art, I feel a piece of work has its worth when it, at the deepest level, serves as a spiritual vector to awaken the mind, or to open the gate beyond which opposites loose meanings, and it’s where the Buddha sits, which is to say, the experience of absolute bliss.

All photographs: permission of Andrew Lam.

Andrew Lam is the author of Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora, which won the 2006 PEN Open Book Award, East Eats West: Writing in the Two Hemispheres, and most recently Birds of Paradise Lost, his first collection of short stories. Lam is editor and cofounder of New American Media, was a regular commentator on NPR’s All Things Considered for many years, and the subject of a 2004 PBS commentary called My Journey Home. His essays have appeared in many newspapers and magazines, from The New York Times to The Nation. He lives in San Francisco.

*

The Poppy: An Interview Series

Four to six questions begin as pods, then burst open with answers, bright lapis,

black-stamened, conspicuous—ornament, remembrance, opiate.

*

This interview first posted at Hothouse Magazine.

THE NEXT BIG THING REDUX

Researching the CAP Marines of the Vietnam War

My gratitude to fellow author and Narrative Story Contest finalist, Lisa Sanchez, for inviting me to participate again in The Next Big Thing, a self-interview series for writers who have recent or forthcoming books, or works-in-progress. While this is my second time around, I'm glad to spread the word of those in my writing community.

In this NBT post, I've answered ten questions about Sybelia Drive, my novel-in-stories, as have my fellow writers on their current books/projects in their respective blogs. We've also included some behind-the-scenes information about our individual writing processes, touching on topics ranging from characters and inspiration to viewpoint and plot.

Please feel free to comment and share your thoughts and questions.

Ten Interview Questions for The Next Big Thing:

What is the working title of your book?

Sybelia Drive

Where did the idea come from for the book?

The backdrop to my entire childhood was the war in Vietnam. To Americans, the Vietnam War. To Vietnamese, the American War. When a child, one thinks that whatever is going on is what has gone on forever. Unfortunately, with war this is mostly true. Given our recent involvement in Afghanistan and Iraq, I wanted to address the many perspectives of those touched by war, from soldiers, deployed and returned, and families stateside, who learn to live inside the wait, to the civilians, those who live within the war-affected areas.

What genre does your book fall under?

Literary fiction. Novel-in-stories.

Which actors would you choose to play your characters in a movie rendition?

Royal – a military-grade Ryan Gosling

Minnie – change her blond pixie to a mess of long dark tresses and her smile to a scowl, and you have Michelle Williams

LuLu – if she can still find her southern accent, the child actress, Taylar Hender

What is the one-sentence synopsis of your book?

In the small lake town in Florida where LuLu, Rainey, and Saul are growing up, life is complicated by war, longing, and conditional love.

Will your book be self-published or represented by an agency?

Hopefully, published by a small press or represented by an agency.

How long did it take you to write the first draft of your manuscript?

About two years. Ongoing research and interruptions of outside short stories, writing workshops, editing work, and my family responsibilities included.

What other books would you compare this story to within your genre?

You Know When the Men Are Gone - Siobhan Fallon

A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain - Robert Olen Butler

Who or What inspired you to write this book?

The Who: A writing teacher once dared me to write a new story when I was having trouble moving forward. I wrote that story and another and another, until I realized the stories were connected and that I was writing a book.

The What: And the realization that nearly everyone I knew in the 1960’s and 70’s had been somehow affected by the war in Vietnam.

What else about your book might pique the reader’s interest?

As a novel-in-stories, Sybelia Drive has the narrative arc of a novel and yet each story stands on its own. Every character has her or his own story, each told from a first-person viewpoint, and so readers will have the chance to experience all sides of the larger story via LuLu, her parents, her brother Saul and best friend Rainey, as well as other characters.

And there you have it!

Thanks to my friends and fellow writers for joining in. Follow the links to their websites to view their NBT responses, which are either already up or forthcoming.

Jennifer Genest is a short story writer and novelist, who I met at the Kenyon Writers Workshop. To me, her writing style is gentle, honest, and forthright with incredible attention to detail and character. Jennifer's novel, The Mending Wall, is the story of small-town hero, John Young, a stone mason whose sterling reputation is compromised after he finds the lifeless body of his teenage daughter's best friend in the woods.

L. Lamar Wilson, with whom I have Florida and Los Angeles Review connections, discusses his newly published Carolina Wren Press winning poetry collection, Sacrilegion, as well as his current project, Missionary. To me, Lamar's poetry contains the presence of Yusef Komunyakaa, the flight of Langston Hughes, the love a mother and a grandmother and all the maternal greats that came before.

Katharine Mariaca-Sullivan, a friend from Lesley University's MFA Program in Creative Writing, is a Jill-of-all-trades in the writing world. Her literary generosity knows no boundaries: artist, writer, teacher, editor, publisher, and more. Her ongoing projects are sure to surprise.

Leland Cheuk and I met during our graduate studies at Lesley University. Stand-up comic and writer, Leland is - seriously, folks - very funny. And so, his novel is bound to be hilarious. Set in the New York City standup scene, WHO KILLED SIRIUS LEE? is a humorous mystery about the search for the lost memoir of a breakthrough Chinese American comedian (imagine an Asian Chris Rock) who has recently died from a drug overdose.

Buki Papillon has completed an interlinked collection of stories set in Nigeria and is currently working on her first novel, River Goddess. A few years ago, I was lucky enough to hear Buki read one of her stories at Lesley University. I remember the story's beautiful images and Buki's gorgeous voice as inspirational.

Bich Minh Nguyen, the author of the novel, Short Girls, and the memoir, Stealing Buddha's Dinner, is working on a new novel. With evocative prose and tender humor, Bich reveals the Vietnamese immigrant experience in completely unique ways.

Ru Freeman is the author of A Disobedient Girl, and will be posting on her upcoming novel, On Sal Mal Lane. Her writing has been described as rich, compassionate, politically complex, and entirely captivating.

Kara Waite describes her current novel, Love is Our Poison, which is engaging and filled with humor and surprises. Kara's story about the inspiration for this novel is wonderful, as is her take on the world.

Ruvanee Vilhauer is working on a collection of stories. Her prose is lyrical and compelling all at once, and questions much about the human condition, in terms of who we are, where we've been, where we are going.