While I wrote the introduction to this interview, outside my study, five men with chainsaws and ropes were cutting down a dying oak tree. Nearly three hours into their work, the trunk was dismantled. Like DOMA. Dismantled. And I admit I considered the analogy, how large and unwieldy an act DOMA was, like the enormous midsection of oak, swinging in the air from the massive claws of a backhoe. If the trunk had fallen onto the street, the impact would have broken the asphalt into pieces. Now that the Defense of Marriage Act has fallen, the impact is considerable. And yet.

What about the thirty-seven states that still do not recognize same-sex marriage? The U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in the case of United States v. Windsor is historic and yet clouded by the fact that the decision will affect gay couples on a state-by-state basis. On June 26th I felt elated, overjoyed for many of my friends; the next day I felt baffled by all the work that still needs doing. Why is awareness so hard for so much of the world?

Of the six writers and artists interviewed in the earlier post, “DOMA and the Arts,” all of them live in states where same-sex marriage is considered illegal and, therefore, they are still inside the long wait for equality. In the original interview, Shannon Cain said, “As a queer artist who draws upon movements for social justice as inspiration and creative fuel, I expect the passage or failure of DOMA to have exactly zero impact on my work.” I wonder now what the others interviewed think of the decision and its impact, and how it applies to their lives as artists. And so I’ve asked several. Joining the conversation is a writer who lives in Massachusetts, where her marriage has been legal since 2004.

Here are their responses.

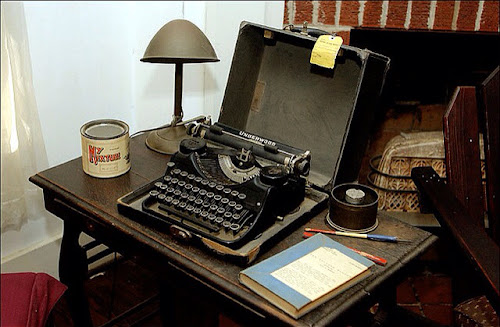

David Covey in silhouette

Photo credit: David Covey

Dave, your work as a lighting director and choreographer has taken you from the Ohio State University’s Dance Department to Europe and several countries in Africa. As an artist and professor in the field of dance, how do you think the dismantling of DOMA will affect the artistry you bring to students and to other artists, nationally and internationally?

Right now I have no idea if the demise of DOMA will affect my work as a gay man, lighting designer, or educator in higher ed. The creative process and teaching, for me, are cultivated through life experiences and hard work. That the federal government will now acknowledge the union of same sex couples legally will probably have no direct impact on my work, or my personal life. I have never personally been a big fan of the institution of marriage, but I am happy for those who choose to be married, that a major hurdle has been removed for the LGBT community, and I hope the remaining states where it is not “legal” will quickly see that they are on the wrong side of history and take action to put this nonsense to bed.

I view the demise of DOMA as a sign that big and important change in attitudes and policy are possible. Given the current state of our government with partisan politics and obstructionist practices where nothing is accomplished and the country continues to pay the salaries of fat, bald, white men who do nothing but advance their hateful policies, in the face of the struggle of so many people, on so many levels, this decision to confirm “gay marriage” stands as a symbol to me that important positive change is still possible.

Over the years I have been fortunate to have traveled and performed across Europe. And last year I spent a month in three countries in Africa. Reflecting on this, the people and cultures in both Europe and Africa have a much different perspective on what happiness and success means. In Europe I was constantly embraced by the openness and generosity of our hosts. Our collective goal was to create art-magic, but unlike here in the United States, where I constantly feel like I am “fighting” to make a creative action occur, in Europe it is part of their collective consciousness. Life is beautiful and together we can make it even more so.

Same thing in Africa, except those beautiful people face a much more extreme existence of life and death—pure survival. What they deal with on a daily basis makes all of the problems we in America face seem incredibly trivial. No food. No water. No house. No doctors. No retirement. No bed. No car. No father. No mother. All dead from AIDS. And we are worried about… what?

But yet again, in working with them to make art-magic, they were transformative in their hunger to learn and graciousness to share. And again, I found this to be core to their existence. The power of art, the power of beauty, the power of connecting to someone who shares in that, is the truth that I have learned, that I embrace, and hopefully will have some influence on the world where we all can live together in peace and love.

This is what the end of DOMA means to me, and how it might affect my work as an artist and professor. We are all equal. And that is the fucking truth. I dare anybody to tell me differently.

David Covey, a professor in The Ohio State University’s Department of Dance, serves as Production Coordinator and teaches dance lighting, production and composition. His research interests include lighting, choreographing and various aspects of visual arts. He received a BESSIE award for lighting BAM Events choreographed by Merce Cunningham in 1998.

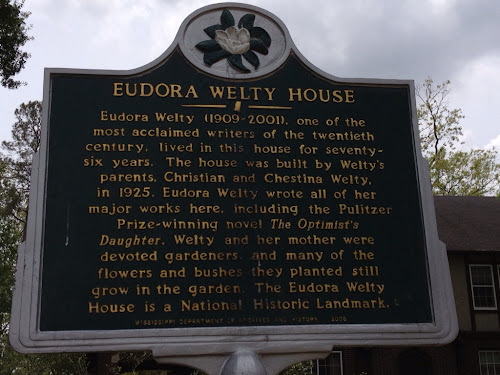

Marlene Robbins – NYC by night

Photo credit: Karin Cecile Davidson

"Because of today's Supreme Court ruling, the federal government can no longer discriminate against the marriages of gay and lesbian Americans. Children born will grow up in a world without DOMA. And those same children who happen to be gay will be free to love and get married, the way I did, but with the same federal benefits, protection and dignity as everyone else." - Edie Windsor - June 26, 2013

Marlene, as a dance specialist, working with 5- to 12-year-old children in a school that relies on the arts as part of the curriculum, how do you think the decision on DOMA will modify your encouraging and inspirational role in the children’s lives?

As I reflect on how the ruling against DOMA may affect my classes at school, I find that I feel at odds with how difficult and complicated the situation still is. On one hand there is a huge step forward, acknowledging the civil rights of all citizens regardless of their sexual orientation, but gay families in Ohio (and 36 other states) still face the same problems. As I work with classroom teachers in creating an integrated curriculum based on studies of our constitution, I think this ruling reiterates that we stand for some things in principle but not in reality. For the children, we as adults have a role and responsibility in working together to make these ideals a reality within the laws of this country.

Marlene Robbins is the dance specialist at Indianola Informal K-8 in Columbus, Ohio. She has a BA in Dance and MA in Arts Education from the Ohio State University, worked as a staff member of the Ohio Arts Council, and received the 2013 Ohio Dance Award for excellence in contribution to the field of dance education.

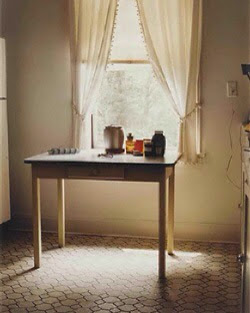

Eliza T. Williamson and Heather Klish

Photo permission: Eliza T. Williamson

Eliza, you are the only one interviewed here who lives in a state where your marriage is recognized as legal. How do you think the dismantling of DOMA will impact you as a writer and an Amherst Writers and Artists writing workshop facilitator?

Heather and I just celebrated our sixth wedding anniversary, and within the month we will be afforded all the rights of hetero married couples. In a very nuts-and-bolts way this will allow us the opportunity to focus more on the creative and less on the bank. For us, the financial impact will be fairly significant because of our tax brackets—which is exciting. I write and facilitate writing workshops based on the method developed by Amherst Writers and Artists (as a certified facilitator and affiliate member). I don’t imagine the ruling’s impact to be earth-shattering in terms of my own writing and teaching, both of which are based on my belief that there is a wellspring of power and magic in giving words to what feels unsayable. The repeal of DOMA goes miles in righting the seventeen-year legal inequities it imposed upon LGBT couples—and I imagine that the absence of legalized bigotry will, over time, impact even the most skeptical in our collective conscience. In that vein, the writers with whom I work may feel less encumbered in their work. That said, we are a long way from achieving equality: this progress marks the beginning again.

Eliza Williamson lives and writes in Metro-west Boston. She and her wife committed to each other for the long haul six years ago, legally in Massachusetts, and in heart on an island off the coast of Maine.

Brad Richard – Motion Studies

Photo permission: Brad Richard

Never ourselves, looking in

on bodies we want to inhabit,

ghosts in a drama of seeing

our desires come close to nothing.

- from "Three Essays on Thomas Eakins' Swimming (1885)"

- by Brad Richard

Brad, you’re an inspiration to your students and an important voice in the world of poetry, LGBTQ and beyond. In what ways do you think the DOMA decision might impact your role as a creative writing teacher, and how will it influence your work as a poet?

I think the decision will further embolden me to encourage LGBT students and their allies to speak up, in their writing and otherwise. That kind of encouragement usually happens by just making sure everyone knows that the classroom (and my school’s Gay-Straight Alliance, for which I’m the advisor) is a space for tolerance. In my own work, I already find myself thinking more critically about these issues. How does one portray desire and love as experienced in a world that still refuses to fully recognize the lived expression of those things—a world in which what’s normal for most straight people is still denied to most queer folks? I don’t ever want to lose the meaningful otherness of queerness—not in life, and not in poetry. On the other hand, I don’t want that otherness to exclude me and my beloved from full participation in American civil life, which is, in fact, the case as things now stand.

Brad Richard – Facebook status on June 27, 2013

To my friends in marriage equality states: yesterday was wonderful, but please don’t forget those of us in the other 37 states. There are still many unanswered questions that are particularly unclear for us, but they basically come down to this: will we be able to fly to one of your states, marry, return to our state, and receive full federal recognition and rights? Until the answer to that is a definitive yes (which it is NOT right now), I reserve the right to remain skeptical and grumpy—although truly happy for you.

Brad Richard is the author of Motion Studies (The Word Works, 2011) and Butcher’s Sugar (Sibling Rivalry Press, 2012). He chairs the creative writing program at Lusher Charter School in New Orleans. He is married to Tim Watson , documentary film writer, editor, producer, and owner of Ariel Montage, Inc.

Tim Watson – Photo credit: Brad Richard

How will the DOMA ruling affect your career as a New Orleans documentary film editor, writer, and producer? And will the ruling’s outcome change anything for the filmmakers you work with and the artists who share creative space in your Bywater studios?

First, let me reiterate my position that the government has no business tying anyone’s marriage and money into a knot; it is taking money from unmarried citizens and giving it to married ones. Further, it causes some people to get or stay married for the wrong reasons.

Now, DOMA’s death: For me and my filmmaker/artist colleagues, a new challenge has surfaced. We have to fight even harder against those in Louisiana who are now working to strengthen our gay marriage ban. If we lose, I fear we (supporters of gay marriage, and gays who want to marry) will begin an exodus to gay marriage-friendly states. We would lose the lives, careers, and artist communities (and workspaces!) that we’ve built here; Louisiana would lose everything we have to contribute; and I dare say life would not be near as fun for those who would remain.

After an 1854 national effort to end slavery, Lincoln detailed the subsequent four years of legislative, judicial, and popular attacks on that effort. He warned against a house divided. So, now, we must not be content with the supreme court rulings on gay marriage; we have to come out slugging.

Tim Watson is an award-winning documentary editor, writer, and producer in New Orleans. He is owner of Ariel Montage, Inc., which produces independent documentary, narrative, and experimental film and video works for national and international audiences. Tim is married to New Orleans poet, Brad Richard.

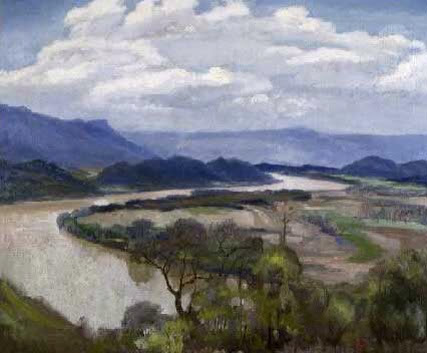

Painting by Val Coradetti

Photo permission: Brad Richard

*

The Poppy: An Interview Series

Four to six questions begin as pods, then burst open with answers, bright lapis,

black-stamened, conspicuous—ornament, remembrance, opiate.

*

This interview first posted at Hothouse Magazine.