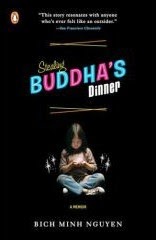

“Stealing Buddha’s Dinner” by Bich Minh Nguyen

“Throughout my childhood I wondered, so often it became a buzzing dullness, why we had ended up here [in Grand Rapids, Mich.], and why we couldn’t leave. I would stare at a map of the United States and imagine us in New York or Boston or Los Angeles… I was convinced people were happier out on the coasts, living in a nexus between so much land and water.” – from “Stealing Buddha’s Dinner”

Bich, now that you’ve landed decades later with your immediate family in San Francisco, a city on the Pacific Coast, do you feel a sense of happiness and possibly a connection—geographical, spiritual, or otherwise—to the distant coast of Vietnam?

I probably felt that way, growing up, because when you live in the Midwest you’re always being told that you’re in the middle of nowhere. Flyover land. But the Midwest—Michigan, Indiana, Illinois—is where I’ve lived the most, and it wasn’t my life’s goal to move to New York or San Francisco. When the opportunity came up, my husband and I really debated it. It freaked me out, really, to imagine living on the west coast, in the Pacific time zone, far from everything I’ve known. Now we’re here in the East Bay and I’m still getting used to it in a sense—getting used to the fact that I chose to change my life. And that our kids are going to be Californian, which seems so strange. I wouldn’t say that living here gives me any particular connection to Vietnam or anything like that. But I do feel more comfortable, by which I mean normal.

Lemon-lavender cake, Twinkies, or a Top Pot hand-forged doughnut?

Lemon-lavender cake. I do love doughnuts though, and almost all kinds of homemade cakes. I love making old-fashioned bundt cakes and layer cakes.

And finally tell us something you’d like to be asked – from inspiration to breakfast to bliss!

Why the obsession with Laura Ingalls Wilder?

When I was a kid I read those “Little House” books until I practically memorized them. I loved the descriptions of food, the cozy evenings, the ongoing battle of farmer versus nature. When I reread the books as an adult, it occurred to me that maybe I loved them because the experiences of the Ingalls family—pioneers moving westward, homesteading, in the 1870s—was not unlike the experience of immigrants moving west to America. They’re parallel stories of heading out to unknown places and starting over. Though Laura and I had nothing in common on the surface, I felt a kinship with her. She knew what it was to be restless, to be shy and bookish, to want to stand out while also wanting to hide. She had longings for certain foods and material comforts. She had a great frenemy. She had secret rebellious thoughts. When I started researching the origin of the “Little House” books, I learned that her daughter Rose had heavily edited, perhaps even co-written, the books. Rose is an obscure figure now, but once upon a time she was more famous than her mother. And late in life she went to Vietnam, as a journalist, in 1965. When I learned about that literal connection between the “Little House” series and Vietnam—this was probably twenty years ago—I knew I would one day write something about it. I just didn’t know what it would be.