“When I was eleven years old I did an unforgivable thing: I set my family photos on fire. We were living in Saigon at the time, and as Viet Cong tanks rolled toward the edge of the city, my mother, half-crazed with fear, ordered me to get rid of everything incriminating… When I was done, the memories of three generations had turned into ashes. Only years later in America did I begin to regret the act.”

– from “Lost Photos” – October 1997 – Perfume Dreams - by Andrew Lam

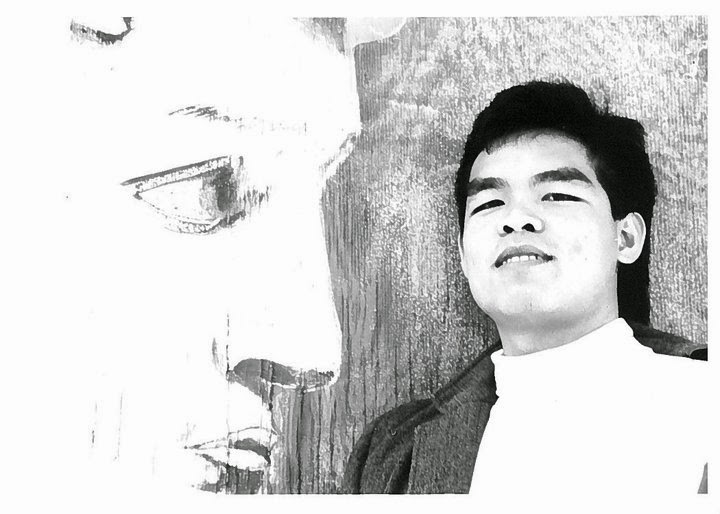

Andrew Lam—journalist, essayist, short story writer—reflects on the world in the way only one who has lost his homeland can: with compassion, understanding, and a global stance. His essays, personal and poignant, examine the Vietnamese diaspora and the bridges and barriers between hemispheres, while his story collection defines the idea of exile in completely new ways. Here, in the first installment of this two-part interview, Lam responds with depth and detail.

Your first languages are Vietnamese and French, and you write in English. It’s not surprising that voice and language play an enormous part in your stories. Do you think your aptitude for these languages carries into your fiction?

Absolutely. I fell in love with the English language, learning it while going through puberty. I am told that children learn foreign languages in the same primal part of the brain as their native tongue, but by high school it becomes a challenge, as brain plasticity has been lost. But in learning a language, your voice breaks, when plasticity is still available and language is both primal and not. That’s how it felt for me. Learning English changed me inside out: I was growing, and my voice broke, and I spoke in a new voice, with a new timbre. It was a kind of enchantment and I never fell out of it.

It helped, of course, to speak Vietnamese and French first. I hear the music in each language, the varying cadences, and the intonations used in different parts of the throat, the mouth, and the nasal area. I can hear voices from many of my characters very clearly – which makes writing short stories like writing plays. And, as an essayist of twenty years, I can hear my own voice very clearly, which makes it less troublesome to write in the third person narrative, that is, when using my own voice for the omniscient viewpoint.

I think I know the answer to this trio of questions, given your travels as a journalist, but readers here might not. And so: Have you ever made a literary pilgrimage? What were your experiences? How did this journey influence your writing?

An interesting set of questions, and the answer to the first is both yes and no. I never intentionally go on literary pilgrimages but have been to places where literature plays a profound role in the experience. Hanoi’s Temple of Literature, for instance, is one of the most beautiful temples I’ve ever visited. Etched on fading tablets atop giant stone turtles are the names of the Mandarins, those of enormous talent and will, who passed the Imperial exams, written as poetry forms, over a thousand years ago. I felt a kinship with these names, for I know the effort to stay awake in late evenings or early morns to write the next sentence, to hear aloud the cadence of your own voice, to get one more line in before darkness takes over.

There are places that remind me of books I’ve read. The Notre Dame de Paris of my childhood brought the memory of reading Victor Hugo’s “The Hunchback of Notre-Dame.” A promenade on the Thames and a visit to Shakespeare’s theatre, The Globe, made me recall “Prospero” and “Romeo and Juliet,” and imagine myself in the audience when the plays were first staged.

At my literary agent’s home in Boston, I was shown some of his prize treasures: door knobs that once belonged to Somerset Maugham, and, of course, I had to touch them, and felt—at least in my own imagination—their razor’s edge.

In Belgium once, through a chance invitation to a castle, my hostess—a Vietnamese woman married to the baron—prepared pho soup and the aroma perfumed the ancient halls. She gave me Vietnamese books to read. It was strange feeling: to be both at home and in a completely strange setting.

But perhaps nowhere have I found the act of writing more powerful than in the Whitehead Detention center in Hong Kong, where I covered the stories Vietnamese refugees who, at the end of the cold war, were facing forced repatriation. The experience became part of my first book, Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora. But it was there, more than two decades ago, that I witnessed the act of writing as a desperate attempt toward freedom. People who were being sent back to communist Vietnam to an uncertain future wrote and wrote. As papers were hard to get, they told their life stories in tiny words so as to save space on a page. They wrote without having an audience. In the end, many gave me their diaries, their private letters, their testimonies and poetry to take out of the camp. These stories, told as a way to convince the UN of their political prosecution at home, could not be taken back to Vietnam, as they would ironically become evidence that they were “anti-revolutionary.” On the other hand, these writings were not admitted by the UN as evidence of those persecuted in Vietnam. I translated and published a few pieces, but the rest sat for years in my closet, a reminder that for some, refugees and persons who sit in a cell, writing is bleeding.

Who are your favorite writers?

I have been influenced by James Baldwin, Joan Didion, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Vladimir Nabokov, Kazuo Ishiguro, Richard Rodriguez, Maxine Hong Kingston, and so many more. I identify with books that I love, and I love these writers for particular books they’ve written.

What is your idea of absolute happiness?

No one asked me this question before, at least, in this particular phrasing. I am not preoccupied with happiness, absolute or partial. It seems to me that it is a conditional state, subject to its opposite, grief and sorrow. Of all these feelings, I’ve had my share. But I will say that for perhaps as long as I can remember, even as a child living in Dalat, Vietnam, my preoccupation is with freedom, in the Buddhist sense. In respect to literature and art, I feel a piece of work has its worth when it, at the deepest level, serves as a spiritual vector to awaken the mind, or to open the gate beyond which opposites loose meanings, and it’s where the Buddha sits, which is to say, the experience of absolute bliss.

All photographs: permission of Andrew Lam.

Andrew Lam is the author of Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora, which won the 2006 PEN Open Book Award, East Eats West: Writing in the Two Hemispheres, and most recently Birds of Paradise Lost, his first collection of short stories. Lam is editor and cofounder of New American Media, was a regular commentator on NPR’s All Things Considered for many years, and the subject of a 2004 PBS commentary called My Journey Home. His essays have appeared in many newspapers and magazines, from The New York Times to The Nation. He lives in San Francisco.

*

The Poppy: An Interview Series

Four to six questions begin as pods, then burst open with answers, bright lapis,

black-stamened, conspicuous—ornament, remembrance, opiate.

*

This interview first posted at Hothouse Magazine.