“If the garden did not hum, it would cuss.”

— from The Garden Will Give You a Fat Lip

by Amy Wright

“Tennessee Roses” – Photo credit: Amy Wright

“I wonder about the promise of love, how it makes none. Something else assures us, for awhile

–the push and pull of the old slipknot–wedding bands and daisy chains.”

- from “It Always Has Hit Me from Below”

- by Amy Wright

Amy Wright – Photo credit: James Yates

Amy Wright rallies and rounds up words, treats long and short lines of poetry to ice cream and fireworks at the fair, and pulls up and down the shades of nonfiction, the stories always bright, never dim. She considers the earth, the spirit, the right or even the wrong way to look for an answer. And from search and discovery, she’s summed up several chapbooks of poetry, a realm of essays and interviews, and the words and the will to till more words keep coming.

Amy once hosted me in Clarksville, Tennessee on a flashflood kind of day, and as we talked, asking and telling, her lithe, well-dreamed, and swimming mind called me to ask more.

“Moving Through It” – Photo credit: James Yates

“It is not the story that makes a moment tender, but the life moving through it.”

- from “Moving Through It” - by Amy Wright

Amy, you’ve found a way to cross under the fence of genre lines, skirting the rough boards, never caught on barbwire, and making sure the essays and poems are tended, but not too tended. You were raised on a farm in southwest Virginia, and your grandparents were dairy farmers, your parents Angus beef farmers. When you were a child, your mother allowed you to read up a storm and told you once, “Sometimes you have to talk to yourself.”

Would you say that your background—the farm, your family—has provided the direction and the eventual path you needed to journey through poetry and prose, verse and memoir?

Absolutely, Karin. That winding dirt road I grew up on and the neighborhood named for it—Mudlick—informs my subject matter, my writing process, and even my genre choices, which demonstrate a refusal of hard and fast lines. Growing up in the country gave me a sense of inhabiting several centuries—the way my grandparents lived in a house that was built by our ancestors in the 1870s with horsehair mortar and locust boards. They added onto it, enclosed the front porch, plumbed a bathroom—but the core of the house, the Heart pine hardwood floors are the same. The fact that this house and my front yard were surrounded by the second oldest mountain range on Earth—the Appalachians—also placed me on a long geologic timeline. The mountains were more than backdrop; they were visiting neighbors. Deer and meadowlarks and box turtles were always popping by.

I’m glad you notice the importance of family in my work. It is probably the most fundamental aspect of my writing—loyalty to the land I grew up on and the people who have given it and me such good care.

“Then there’s this” – Photo Credit: Amy Wright

“so thereʼs that, so thereʼs that, so thereʼs this and this and that”

- from “Then There’s This” – by Amy Wright

Farms, gardens, the earth, sustainability, sustenance. What we collect, what we can’t keep. Spirituality, devotion, Zen, impermanence, letting go.

You are deeply concerned with where we’ve been and where we are headed in terms of the environment, farming, and making sure, as the world population grows, that we are all fed. These concerns inform much of your writing. Would you talk about this?

I am fortunate to have developed a relationship with nature early on. My brother and I played in the southwest Virginia hills and forests around our house. At least once, we had to walk back to the house barefoot on gravel because we mired our tennis shoes in the mud of a shoestring branch. We climbed shale banks, fished for bluegill, planted gardens, pulled weeds, snapped green beans, etc. Many summer nights we sat down to meals where we had grown every food on our plates—including cantaloupe or watermelon for dessert. That magic moment when a corn shoot breaks free of its seed, climbs through dark soil toward the light—sometimes alarmingly far away when one of us pushed the seeds too deep—filled me with wonder then and now. I know our tremendous debt to Earth for producing food, plumping it with minerals our bodies need. And to we owe the many humans present and past whose labor and invention make it possible to stock a grocery store.

It’s like the difference between falling in love with an abstraction and a man who snores. If I had not had the planet’s topsoil under my fingernails and its well water popping in beads from my forehead, I don’t know if I would have begun to care deeply about its health. When I read about a polluted river or a scalped mountain, I have brain cells and neurons that fire in response. Such scenes correspond in my body, making the causes and effects tangible and the need for responsibility real.

“Hands” – Photo credit: Susan Bryant

“I remember when I loved to be sad. I could feel sorrow coming on

like a cold, which I also had my fair share of in those days.”

- from “Perhaps It Is Only Age” – by Amy Wright

“Oh, Heart” – Photo Credit: James Yates

Life. Death. Life.

I love what you’ve written in “Oh, Heart,” an essay you posted at Cowbird: “If John Keats was, in his youth anyway, ‘half in love with easeful Death,’ I am absolutely swept into the clench, the hiccup, the cough of Life.”

Death is the hardest, but sometimes life is hard for those who go on living. More thoughts?

That particular piece—in a small way—gave me a taste of those fifteen minutes of fame Andy Warhol promised everyone in the future. I collected so many “loves” on that essay, it stopped feeling like something I did as much as something I was taking part in—the way you might get swept into the momentum of a parade. Of course, I owe the photographer, James Yates, for the image, which spoke to so many other heart-heeding humans.

But, to answer your question, I feel I owe it to the ones I’ve lost to live fully. My younger brother died of bone cancer at twenty. To honor his memory, I try to be vigilant in attending the resources pumping through my irises, cochlea, fingertips. He asked me to do as much before he left.

“Hair Flying” – Photo credit: Susan Bryant

“the terrific blue, the movement of the hands upraised and hair flying”

- from “Fearlessening”– by Amy Wright

Sunflowers, amaranth, or salmon-colored orchids? And why, oh, why?

For the same reason species can evolve, metamorphose, mutate—because there are those of us who can taste words and there are those who can season them. It’s like canning. There are ways to preserve the sun-ripened bounty of a mulberry harvest for a February night.

“My Boon Companion” – Photo credit: James Yates

“We are never alone, johnnie; we are only–for varying stretches of road–entirely together in ourselves.”

- from “My Boon Companion” – by Amy Wright

I understand your latest project involves heritage as it threads from past into present, with a close look, as you’ve noted, at “one particularly marginalized and unstudied culture” in the south.

Would you tell us more about these poems? It sounds as though you may be crossing poetry with memoir, creating a hybrid of forms. Is that true?

I have long been interested in the relationship between research and creativity, and my scholarly essays and travel pieces reflect that. Recently I’ve been applying that dimension to the lyric in the form of anthropological case-studies of my life’s characters and stories. I’m interested in how cultural diversity can be threatened alongside many wildlife species. Thus, I want to preserve aspects of the culture I inherited, even as I have revised some of that conditioning.

My father learned to cane chairs from a blind man. My great-grandmother dipped snuff and taught school in a one-room Appalachian schoolhouse. Both of these facts seem akin to spotting a red-cockaded woodpecker, and equally worthy of attention. So, I’m wedding a few reference books to memories and running them through that great Victrola of the English language until something catches in my head like a tune.

Amy – Photo credit: David Iacovazzi-Pau

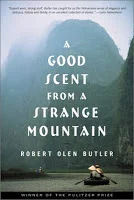

Amy Wright is the Nonfiction Editor of Zone 3 Press and the author of three chapbooks, There Are No New Ways To Kill A Man, Farm, and The Garden Will Give You A Fat Lip. Her fourth chapbook, Rhinestones in the Bed, or Cracker Crumbs is forthcoming from Dancing Girl Press. Her work also appears in a number of journals including Drunken Boat, Freerange Nonfiction,American Letters & Commentary, Quarterly West, Bellingham Review, Western Humanities Review, and Denver Quarterly.

Read more of Amy’s poems and essays at Cowbird.

http://cowbird.com/amy-wright/

“Leaning Back” – Feature photo credit: James Yates

*

The Poppy: An Interview Series

Four to six questions begin as pods, then burst open with answers, bright lapis,

black-stamened, conspicuous—ornament, remembrance, opiate.

*

This interview first posted at Hothouse Magazine.