SYBELIA DRIVE ARCs have arrived, pre-order links are up, & only two months to go until the novel’s release date of October 6th! Artist & true friend, Annie Russell, created the most beautiful cover I could ever imagine, & the Braddock Avenue Books creative team coordinated design, edits, & all the rest. When I started writing this novel, I wrote on a dare, I wrote to answer questions I’d had for decades. LuLu showed up, then Rainey, & of course, Saul. I wandered after them into the citrus groves of childhood, trying to know the bitter scents of fallen fruit, of fathers & sons sent away to war, of mothers trying to make ends meet. I’d love to share their story, so here is the PRE-ORDER LINK. Braddock Avenue Books, the small press that gave this book a home, will benefit the most from pre-order purchases. From now until the beginning of October, they’ll earn 50% of the sales price, but once Amazon takes over, the press will earn a little less than a dollar. Pretty sobering. Is it a leap of faith to ignore discounts & convenience? I hope so. Braddock Avenue Books will thank you, and so will I! Plus you’ll get a memorable read, or the most gorgeous doorstop you’ve ever seen, and my ever-loving gratitude. 💕🌸

New Voices: The Weight of Words & The World of Aftermath

C. Morgan Babst

Everything, Even Love, Even Home: An Interview with C. Morgan Babst

Lush with the scents of ligustrum, a fallen magnolia, an evening breeze off the Mississippi River, New Orleans author C. Morgan Babst’s debut novel, “The Floating World,” sings the world of aftermath—of devastation, desire, the city’s dead. Here is the city of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, above and beyond the ruptured levees, inside the psyche of a family wrought with longing and despair at the sight and reek of their drowned home. The five members and three generations of the Boisdoré family reveal this story in ribboning, intersecting storylines, emphasizing the truth of the novel’s epigraph from Virgil’s “Aeneid”: “Each must be his own hope.”

Hilary Zaid

The Weight of Silence, The Weight of Words: An Interview with Hilary Zaid

Bay Area author, alumna of Harvard, Radcliffe, and UC Berkeley, Hilary Zaid surprises, and her debut novel, “Paper is White,” is indeed an astonishing and successful surprise. Balancing weighted subjects with blue skies and beautiful slices of cake, with wedding arrangements and secret encounters, Zaid measures out humor with generosity, hope with passion, even grief with impossible understanding. Through narrative spun in first person, lead character and heroine Ellen Margolis finds her way in late 90s San Francisco, where elderly Holocaust survivors reveal their stories, relationships grow close and become divided, and the past lies like a wedding veil across the future.

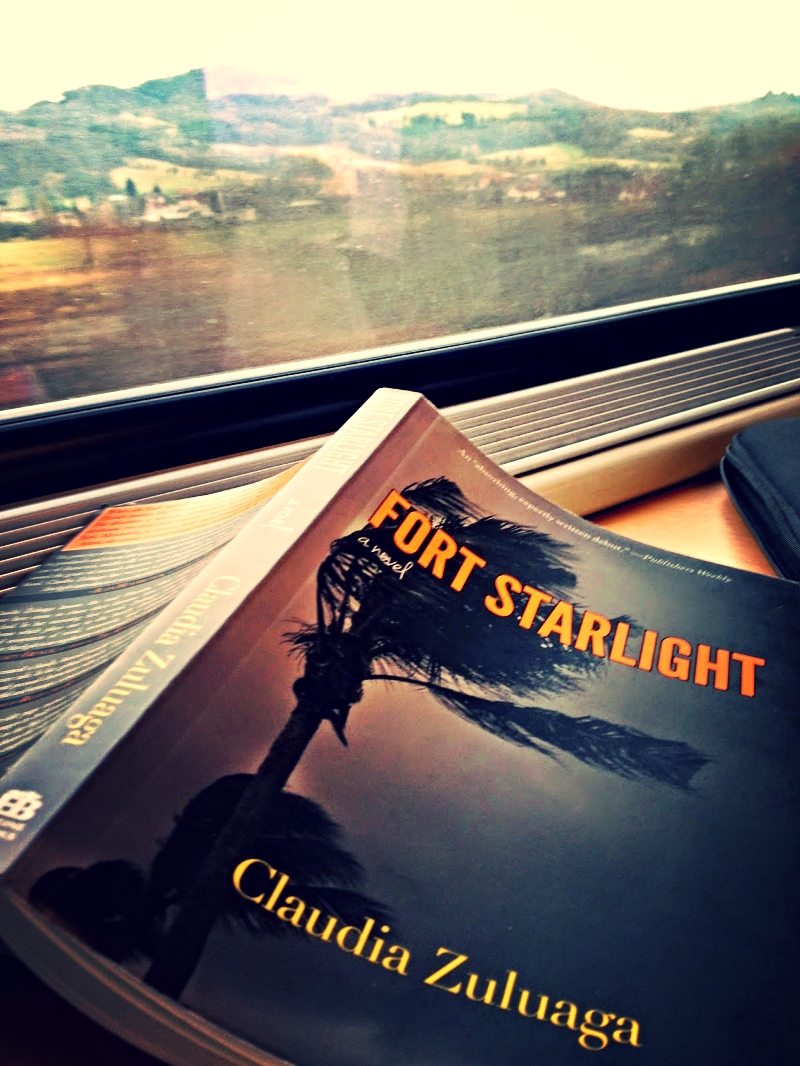

Fort Starlight: A Florida Story

reading Fort Starlight en route to Prague

When traveling by train from Berlin to Prague, I began reading Claudia Zuluaga’s debut novel, Fort Starlight. Immediately caught up in the Florida tale of lost souls, swampland, and strangely discovered dreams, I was startled every now and then at the sight of cliffs and castles outside the train windows. Perhaps I was missing the sights of central Europe, but this is typical of me—I head off on adventures and find myself longing for home, which means “the South,” specifically the age-old stomping grounds of Florida. And so, Claudia Zuluaga’s words gave me permission to do just that, with a story that calls up uniquely believable characters, a vibrant and true sense of place, and just the right sway of narrative voice to carry the piece from start to finish. Engine Books’ editors, Victoria Barrett and Andrew Scott, have their sights set on fine writing, and Fort Starlight is among their many well-received titles. Curious about the author’s inspiration, the novel’s themes, and the astounding writing that adds Fort Starlight—by The New York Times Book Review’s standards—to the latest shelf of “Southern Literature,” I asked Claudia if she’d consider an interview, and I’m thrilled that she said, Yes!

Port St. Lucie, Florida

“past the beach houses built on stilts”

“Past the Beach houses built on stilts, past the ocean highway that runs along Erne City, past an inlet that is a shade lighter than the ocean, past more houses, past small streets, past the Florida turnpike, past dark clusters of trees, two North American blackbirds, male and female, fly west over the southeastern shore of the Florida peninsula.”-Claudia Zuluaga

The prelude to Fort Starlight—a novel about leaving the familiar and discovering the unfamiliar, about isolation and longing, about desperation and dreams—is one of place, and our first view, reminiscent of Eudora Welty’s opening passages in “A Curtain of Green,” is from above, an aerial shot of that place in Starlight County where the story will unfold.

The wetlands and heat and flat brilliance of Florida’s east coast are familiar to you, Claudia. Could you tell us a little about your background, how you, too, once found yourself in Florida, and why this setting is integral to your main character Ida’s story?

I’m the sixth of seven children. I was born in White Plains, NY. My parents, who had never owned a house, had bought a parcel of land in Florida around the time that I was born. I don’t think it was ever worth much, but the summer before I turned sixteen, when all of my older siblings were living on their own, they traded that plot of land toward the purchase of a villa in Port St. Lucie. At that time, Port St. Lucie wasn’t fully developed, and there was nothing but wilderness to the west of our planned community. Only maybe half of the villas were occupied, and for a teenager, pulled away from her friends and her pedestrian life, it was profoundly disorienting. And the heat. The whole thing felt like a dream. I would try to go for a walk, but five minutes in any direction was just swamp, tall grass, or asphalt, rippling in the heat. I spent most of that summer, after I gave up on the walking, inside the villa, in the air conditioning.

I was only fifteen, and my parents had put everything they had into starting a life there, but all I could think about was that everything I had known, all the people I had known, were gone, and I had to find a way to make something for myself, because I couldn’t imagine anything coming next. It seemed, at that point, impossible. And then, like Ida, I realized it was something I’d just have to survive, and that maybe I’d never know what it meant. But I did find things to hold onto. I made friends. I made it work as well as I was able. It didn’t take away my urge to escape, to undo what I felt had been done to me, but I found beauty there. It is beautiful.

North American Blackbirds

The blackbirds, first introduced in novel’s beginning pages, appear throughout, at first to show us the way and then, more than literary device, more than motif, they reveal their own story. Like the characters of Fort Starlight, they, too, are trying their best to survive the harsh and beautiful wetlands, “a place where anything dripping and new could step up out of the muck and begin its existence.” And inside the act of survival we witness the imperfections and vulnerabilities of the creatures and characters.

Would you expand on the importance of the world here, “the seven square miles of muddy rivers, scrubby trees, swamp, the forest hammock,” in relation to your characters and the intertwining stories?

The world of south Florida, of this wild part of south Florida that doesn’t touch the Atlantic, is something you can’t deny, can’t get away from. There is no ocean breeze to cool you off, no reassuring smell of salt in the air. It’s something that makes you think, “People probably aren’t supposed to be living here.”

But they are. And they are in Fort Starlight. Nature has pushed (almost) everybody inside to shelter, and inside is where they have to deal with their weaknesses, their problems, their pain. The place makes me think of a sweat lodge, somewhere you go to sit and sweat and suffer, all for the purposes of purifying, of moving forward.

A friend of mine says, “You can’t get away from your shit. It’ll track you down and eventually make you deal with it.” Everybody in Fort Starlight is at that place in their lives. They can’t run any longer. This is what unites all of the characters. This is the basis of their community, whether they know it or not.

“An alligator could snap you up in two seconds”

“the body of… a twelve-year-old boy is guarded by a thirteen-foot alligator”

As I read Fort Starlight, I noticed the idea of imperfection casting itself into the storylines, and in each successive chapter, with subtlety and great care, the perfection of imperfection beginning to fold itself into scenes in which characters interact with each other and with nature. Careful narrative threads, crosscutting, and lyricism work together and create a landscape in which the perfection of imperfection is revealed. Pairings appear: Ida and her long-lost brother, Peter and the memory of his wealthy father, the at-odds gay couple Ryan and Lloyd, the neglected and wandering boys Donnie and Carter, Nancy and her terminally ill great-niece, even the body of twelve-year-old Mitchell Healy and a four-hundred-pound alligator, and yes, the blackbirds.

What might you tell us of the meaningful isolation and imperfection of your characters and of the physical, emotional places in which they find themselves?

I wanted to make Ida stuck, with no easy way out. The only way she is going to grow, meaningfully, is by being stuck with herself. It is so tempting to think that everything will change, if only you pack up and move away from the familiar, if only the background and the noise and the weather are different. Of course, it’s not that easy. The only things that change are the background, noise, weather. As soon as the disorientation has dissipated, you are back where you started.

Despite the difficulties that Ryan and Lloyd are having, that Nancy and her great niece are having, that even the boys are having, they all have each other for support in their journey. Ida has only the imaginary companionship of her brother. Peter has only the memory his father and the illusion of his superior intellect. These two are the most in need of figuring out who they are and how their lives are going to be, and both are brave about it, if a bit misguided. They have to be alone, until they don’t anymore. And I see their relationship—one of parallel growth rather than intimacy—continuing beyond that last moment at the beach.

Florida tree house

Tidal pool, tree house, or a beachside table spread with a sunset supper of cold white wine and deep-fried gator?

I’m torn between the tidal pool and the tree house. When I was in high school, we would go to a beach called Bathtub, and when the tidal pools were full and warm, at night, we’d bring goggles. You could swim in some of these pools in darkness, without having to worry about riptides or sharks. There were these phosphorescent organisms, and if you moved your hands underwater, watching with the goggles, it was like you were parting the stars. Amazing.

One of my brothers moved to Florida for a few years, around the time I moved out of my family’s home, and he and his wife did live in a tree house for a time. It was tiny, dark wood, with bunks instead of beds, no real furniture. Something from a fantasy movie, like The Dark Crystal or Labyrinth. It wasn’t open to the elements, but it was up in a tree, up over swamp water, cozy. He moved there with his wife, just after they were married.

Florida map

Claudia, you’ve lived in the South, and your writing, so far, concerns the South, a place that for many, including myself, has a mystical, powerful, sinkhole kind of attraction. There are the harsh realities of hurricanes, overzealous religions, and unsettling heat, and then there are the gentler ones of salty ocean breezes, herons in flight, the taste of grilled pompano.

Do you find that you are drawn still to writing mostly about Florida? What is it about this particular setting that inspired you to write the Pushcart-nominated story, “Okeechobee,” and then the much-praised novel, Fort Starlight?

There is something in the very shape of Florida that makes it feel cut off from the rest of the country, the rest of the world. Once I moved there, I never once drove up and out of the state. It just seemed so far. We’d go south, west, east. Never north.

I moved to an efficiency near the beach just before I turned nineteen, and then to Orlando for a few years, where I worked as a waitress. As a matter of fact, I didn’t leave Florida until I was twenty-one and flying out on my very first airplane ride. I’ve never been back to my home town. Not even once. Miami, the Keys a few times, but no more Treasure Coast. This wasn’t on purpose. I didn’t really feel I had roots there, and even my parents gave up and moved back north, because none of their children lived down there.

That isn’t to say that Florida doesn’t have culture or joy or possibility, because of course it does. I think my feelings about that particular part of Florida were really colored by the fact that, when I did live there as a teenager, I was under the thumbs of my strict parents, and I had no car or freedom. I was away from everything I’d ever known and believed the rest of the world was gone; there was no evidence of it anymore. I couldn’t even go for a walk, because there was nothing to walk to. I couldn’t get my bearings, really. All of this combined made me really disoriented and unsure about how to figure out who I was. I fled, thinking I needed the distraction of other people to be able to figure it out. Maybe I did.

Now, I’m a grownup, I can drive, and there’s the magic of the internet, connecting everybody. The place I lived, as I knew it then, doesn’t exist anymore. I wouldn’t experience it the same way.

I didn’t realize I had to get it out of my system, work through what it all meant, until I was in the noise and chaos of New York City. People have described my writing as atmospheric, very setting-oriented. I’m not sure if that is the case in anything I write that isn’t based in Florida. I think I may be done with Florida, but who knows! I have other Florida stories, one called Be Your Animal, published in the now defunct Lost Magazine.

Okeechobee

Trailers & Palm Trees

At David Abrams’ literary blog, The Quivering Pen, you wrote of earning your first paycheck for a story accepted by Narrative Magazine. I love the humor and honesty of this account, and even more, I love the story itself. “Okeechobee” is a sweet, sad short-short about how childhood and family are rough and rare.

Would you tell us something about the narrator, a young girl who notices the world around her—her own version of Florida—in terms of the tension between her parents, the hot afternoon of canned colas and closed trailer doors, curses and class differences and broken-down cars?

Kids take in what they are ready to take in. There is an age when children start noticing the things that are not right about their lives, not right about their families. They start to imagine what their own life will be like someday, and this causes them to notice and judge and long for what they don’t have. My narrator has just begun to have this awareness. She sees the tension between her parents, the lack of joy, affection, spontaneity, and starts to put the pieces together, trying to figure out where it all came from, trying to figure out what it means for her.

My second summer in Florida, I had a boyfriend who seemed to be, at the time, the only thing I had going for me. Naturally, he dumped me. I was despondent, because I had thought I’d found some direction, something to hold onto that made me who I was. If I mattered to someone, then I was connected to the world. The dumping happened around the time my mother wanted to visit her friend in Okeechobee, and though I was a mess, she made me come. Maybe she thought it would cheer me up, or maybe she just was wary of leaving me home alone. We got in the car and drove, meeting her friends at a rodeo (where they did, I think, have warm cans of cola). It was so hot. I thought it was supremely ugly. I sat with my shoulders hunched, too numb to cry.

A bull collapsed. People rushed over, then just stood over it, watching while the beast’s heart gave out. It seemed that there could be no more miserable place on earth at that moment. Hot and dusty, warm soda, a heartbroken girl, a dying bull, all of this happening even closer to the center of the state, where there seemed to be no escape. Why had my mother made me come? Did she not understand my despair? There was definitely something about the disconnect that inspired the story of Okeechobee.

“Small fishes, sand, bits of seaweed, scallop shells, whole and cracked”

And finally, I want to acknowledge the ending of Fort Starlight without giving it away. There are moments of resolution I feared might become too carefully tied, and so I was relieved that the characters and their story lines remain a bit smudged, as well as lovely and imperfect. Ida’s character expands exponentially once she finds the Atlantic, and as in the beginning, she experiences a new place with “tide pools on both sides… the water… so clear… [she] can see the bottom… Small fishes, sand, bits of seaweed, scallop shells, whole and cracked… a stingray in the last… just before the sand bars end and the open ocean begins.” Here, there is a widening, the possibility of moving forward, the moment Ida and all Fort Starlight’s characters have longed for. Is this perhaps where you as a writer also found a place from which to move forward? And from this easterly view, where are you headed next?

Yes!! I am working on a novel right now that goes to an even more challenging place for me, emotionally and psychologically. Before Fort Starlight, I wouldn’t have had the courage to jump into the strange, unknowable thing I’m jumping into now. Now I trust the process of writing a novel and know that it will work itself out, as long as I keep at it. Fort Starlight was a mess for years. I had all of these pieces and had no idea how they connected. For the longest time, I couldn’t figure out who Ida was. I would see her doing things and I didn’t know why. All I had was atmosphere, and it took so long for the people to emerge from this atmosphere, and this is echoed in the prologue with the bit you excerpted: “a place where anything dripping and new could step up out of the muck and begin its existence.”

So I’m looking east, yes. At the deepest, darkest, most unknowable trenches of the ocean. With my fingers crossed.

CLAUDIA ZULUAGA

Photo Credit: Christian Uhl

Claudia Zuluaga is an English Lecturer at John Jay College (CUNY) in New York City. She received her MFA in Creative Writing from Sarah Lawrence College. Her short stories, which have been nominated for Pushcart and Best American Short Stories, have been published in Narrative Magazine, JMWW, Lost Magazine, and Linnaean Street.

*

The Poppy: An Interview Series

Four to six questions begin as pods, then burst open with answers, bright lapis,

black-stamened, conspicuous—ornament, remembrance, opiate.

*

First posted at Hothouse Magazine.

six - plus ONE - things about me

1. The one and only time I tasted coquina stew was at New Smyrna Beach in 1965. Salt and sand.

2. In 1968, I'd ride my Schwinn through the cemeteries in New Orleans, already knowing enough about the dead not to be scared.

3. I still love to wait for parades. There aren't enough parades in this world. Obviously, I need to move back to New Orleans.

4. My father, like Popeye, was a sailor man.

5. Fluid in the ear is no joke. I now know why babies with earaches cry and cry and cry.

6. I love words more than fallen leaves.

and because in NOLA we love lagniappe - a little extra:

7. I'm looking for a coastline to call home.

The Gaze of Emilie Staat

“But tango begins before the dance, with a subtle yet terribly important gaze I haven’t yet

mastered. The cabeceo is an invitation, without words, and involves direct and sustained eye

contact, often from across the room. If a leader catches the eye of a follower and nods to the

dance floor, he is inviting her to dance. If she maintains the eye contact, smiles, or nods, she has

accepted. This is perfectly elegant in theory, but fraught with peril in practice.”

- from Emilie Staat’s memoir-in-progress, Tango Face: How I Became a Dancer and Became Myself

Portrait of Emilie by French artist Gersin

Emilie Staat surprises me. Her gaze is open, and her conversation eager and engaging. I’ve come to know her as an incredible reader and editor, and on a sunny May morning in New Orleans, I listened to her stories and later read a few chapters of her memoir-in-progress. Her written words have taken me by surprise all over again. Here, she reveals her love of tango and how the dance has led her on a journey of self-discovery.

Emilie Staat & Casey Mills perform at the 2012 Words and Music Literary Festival – Photo Credit: Sheri Stauch

Emilie, in your award-winning essay, “Tango Face,” you write of the cabeceo, or unspoken invitation to dance, the difficulty of the gaze, the “initial awkwardness” that comes from “the proximity of the embrace.” As a writer, language is your strength. How is the experience of moving into the world of tango, a world with a completely different vocabulary, nuanced and wordless, a world that you describe with thoughtful, passionate prose, deepening your work as a writer?

Originally, I thought tango would help me better understand the main character of my novel, a circus performer who has a visceral relationship with the world that’s very different from my own. And tango did increase my understanding of her physicality. But it became less about research and reached me personally. I think it has made me more generous and empathetic as a person, because you can feel your partner’s nervousness, or distraction, or happiness in their body as you dance together. It’s hard to dance that closely with someone for ten or twelve minutes without feeling connected to them. I’m also more aware of how wrong I often am about what people are thinking or feeling. My best interpretation still contains a seed of me—my experiences, prejudices, and assumptions filter my interpretations. Knowing that helps me set aside the me more cleanly and think about them—my partners, my characters.

In my work, tango has given me a new set of tools, changed my syntax, made me more mindful of the effect the words I choose will have, maybe like music. Recently, I had the opportunity to take workshops with Silvina Valz and Diego Pedernera while they were in New Orleans, including one focusing on the chacarera, a folkloric dance from Argentina that is vastly different than tango. I was struck by the fact that the whole dance is a working toward an embrace at the end. Instead of the intense embrace of tango, there is eye contact as each dancer performs their part, eye contact that becomes itself an embrace. The chacarera made me reconsider the cabeceo, my struggles with it and how intricate and elegant nonverbal communication can be and by contrast, how purposeful and powerful your words should be.

Silvina Valz & Diego Pedernera perform in New Orleans at La Milonga Que Fatalba

“How did I end up… surrounded by $800 worth of shoes, both excited… and terrified of them?”

– from “Comme il Faut,” an essay-in-progress by Emilie Staat

Tango, two-step, or tarantella?

I had to look up the tarantella because I had only a vague notion of what it is. Not that I know much more now, but what strikes me most is that it seems like a dance that is much harder than a casual observer would think. Which is true of most dances, that they are easy to do, but difficult to do well. There is an enormous gap between the verb and the noun, so while I love dancing other styles like two-step, salsa and swing, tango is the only dance that has made me a dancer.

Cicely Tyson

Ernest J. Gaines

When you were awarded the gold medal for “Tango Face,” the Faulkner-Wisdom Nonfiction Prize

winner, the organizers of the Words and Music Literary Festival invited you to perform. Would you tell us about the experience of dancing the tango on the same stage that writer Ernest J. Gaines and actress Cicely Tyson had just shared?

I’d only been learning tango for about a year, and while I was a good beginner, I wasn’t at performance level. When Rosemary James, who organizes the festival, said I should perform, I said no at first. But then, every night for a week, I dreamt about performing. I knew the room, I knew who my partner would be, what dress I would wear and what song we would dance to. Every night, it was such a vivid dream, and I realized how badly I wanted to perform, even if I wasn’t ready. When I asked Rosemary if it was too late, she was utterly gracious and suddenly, everything that seemed like a problem fell away.

The night of the performance, I was humbled by Cicely Tyson’s incredibly intimate and commanding performance and when Ernest Gaines spoke about his career and Faulkner, I was standing just alongside the stage, waiting with my partner to go on, but also just a few feet from what was, and felt like, a very important literary moment. The writer in me, analytical and cerebral, came forward and pushed the dancer back. I got in my head at the worst moment and I was so stiff and terrified. What I like best about the photo of our dance is that Sheri caught the instant, nearly a minute into the performance, that I utterly surrendered to the experience, to the song and to my partner.

Louisiana graffiti

Emilie Staat, director Steve Herek, & actor Jose Zuniga worked together filming “The Chaperone”

As is typical of most writers, you have a day job and an intriguing one at that—as a script coordinator on films such as Twelve Years a Slave, Oldboy, HBO’s True Detective, Now You See Me, and 21 Jump Street.

But your work is far from typical in that film projects can last for intense and long periods, and once they are complete, you take off a block of time to write. Would you tell us about your experiences in some of these projects? The highs, the lows, the stamina needed to survive long hours. And is the balance of all film work and then all writing working well for you?

Sometimes, I think my day job is too interesting, too distracting, and it doesn’t allow me a lot of time to write. But it does satisfy something necessary and I’m building toward a future in film that is more creative. I can’t quite give it up because my entire being lights up when I get a film job, or when I watch a movie I worked on. When I’m not working on a film and I pass by a set, I feel a pang. So, as all-consuming as that life is, I have to make space, find balance. I worked two of my biggest, longest shows (Now You See Me and Twelve Years a Slave) back to back in the year I first started to learn tango. I think it was my way of socializing, having something of a life, because it’s easy to lose that while working. But it also sparked my creativity, fueled my imagination in ways I didn’t expect. I’d been seeking balance for a long time, and tango forced me to work on it in a very real way that filtered into every aspect of my life.

Umbrella Tango in Times Square

Favorite place to write/dance.

For the first five years I lived in New Orleans, I wrote almost exclusively at a coffee shop by my house, which closed on New Year’s Eve almost two years ago. We jokingly called this place Cheers and it was a lot like Central Perk on Friends, very central to my life. Several people asked me if I was going to move when it closed (it took me more than a year, but I did move). I have a tendency to get rooted in one place. So these days, I’ve embraced the rootlessness of not having a steady writing home. It makes me more flexible and more focused on what I bring to the table each day, rather than where I write.

The same is true of my dance venues. There are aspects I appreciate about all of them, but I’ve yet to find a spot that is a perfect combination of elements – floor personality, space, temperature, music, crowd, etc. But I enjoy them all and I try to focus on my dance, rather than the limitations or advantages of the particular space.

Favorite writing tool/tango heel.

I’m ambidextrous in my writing tools. Sometimes I write by hand, very often I type. My iPhone is a tool and so are physical journals. Shoes are similar. My first pair of tango shoes were a pair of suede Comme il Fauts, which many consider the top of the line, with steel-reinforced heels. I call these my “old faithfuls” now cause they’re so worn in. My main pair currently are silver and black Darcos heels that are very sexy and go with everything.

Favorite writer/tango dancer.

I appreciate so many writers and dancers for the things they do particularly well, or what they have to say about craft. And, in both writing and dancing, my favorites have changed as I’ve matured and learned more about myself.

My favorites in my dance community are often people I’ve danced with many, many times and we’ve developed a style, almost a language, together. One of my favorite dancers might be a man I danced with only once, when we were both visitors at a Chicago dance event, and who I’ve never seen again. Or maybe that’s just one of my favorite dances.

I’ve been lucky enough to learn from world-class professional dancers who visit New Orleans, couples like Homer and Cristina Ladas, one of the first visiting couples whose workshops I took. They’re coming back to New Orleans in December for a mini tango festival, together with Ney Melo and Jennifer Bratt, and we’re incredibly lucky to have those two couples visit our community.

As for writers, I’m forming my “memoir tribe” now, with fierce writers like Cheryl Strayed, Melissa Febos and Claire Dederer. I just finished reading Rob Sheffield’s Turn Around Bright Eyes, and I’d definitely put him in my tribe. Dean Koontz and Alice Hoffman are both long-standing favorites who I’ve read since I was a teenager aching to be a writer and they have really formed me in immeasurable ways.

At present, you are working on your memoir, Tango Face: How I Became a Dancer and Became Myself, and you also have a novel-in-progress, The Winter Circus, in the wings. What are your dreams—in terms writing time, space, and subject—for the future?

I’d like to get these two books out into the world, of course. The novel’s been in my life since 2004 and now I’ve been working on the memoir for almost two years. There are more projects in the queue that I’d like to get to, including two t.v. shows and a feature script I co-wrote earlier this year. And as much as I love New Orleans, I miss traveling and I’d like to make it a bigger part of my life. A friend and I are discussing taking a road trip to all the major U.S. tango cities next year, maybe even turning it into a blog or film as we go. We’re looking into crowd-funding, so we’ve been working out the budget and which cities we’d visit. It’s starting to feel like a very real possibility.

Emilie’s Banksy tattoo

& Banksy’s original image

Lagniappe question!

I remember your fascination with graffiti artist Banksy, and your story about getting a Banksy tattoo. The image reminds me a little of your view of the world, holding on and letting go, as in dance and writing. Would you share that story?

I have five tattoos, which I got between the ages of 25 and 30. My tattoos, the project of picking what I would permanently display on my flesh, is about making myself at home in my body, which I struggled to do throughout my teens and twenties. Each of the images is a reminder to myself. Your comment about holding on and letting go is perfect. I’ve never thought about it precisely like that, but I’ve always liked that Banksy’s image is both positive and pessimistic, depending on who is looking at it or where they are in life, or at the moment they see it. It’s about yearning and losing, childhood and hope, love and nostalgia. Contradiction and complexity is what makes it such a fascinating and universal image. It’s the closest to an “off the wall” tattoo I have, since it’s someone’s art exactly and not an image that I designed with the tattoo artist. Yet, you’re right that it does depict my world view.

Emilie Staat

Emilie Staat’s essay Tango Face won the 2012 Faulkner-Wisdom Nonfiction Prize. She is working on a memoir about life and tango under the same title as well as a novel. When she is not working as a script coordinator for film and television, she writes book features for 225 Magazine and blogs at NolaFemmes and her personal blog, Jill of All Genres.

Feature photo: Emilie Staat – in the French Quarter, at the Words and Music Festival, New Orleans Photo Credit: Che Yeun

*

The Poppy: An Interview Series

Four to six questions begin as pods, then burst open with answers, bright lapis,

black-stamened, conspicuous—ornament, remembrance, opiate.

*

This interview first posted at Hothouse Magazine.